Princes of Afan

- Princes of Afan

- Chapter 1: Villains or Heroes?

- Chapter 2: Seals of Office

- Chapter 3: The Aberafan Charter, c.1306

- Chapter 4: Where they lived

- Chapter 5: Where They Worshipped

- Chapter 6: Other Local Sites Associated with the Afan Dynasty

- Chapter 7: Ieuan Gethin and Other Poets at Plas Baglan

- Chapter 8: Time Line of Events Relating to the Princes of Afan

- Chapter 9: Princes of Afan in the Wider Context

- Chapter 10: The End of the Dynasty at Aberafan

Chapter 1: Villains or Heroes?

The defeat of the Anglo-Saxon king Harold by William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 is embedded in the mind of every pupil studying British history as being the date the Normans took control of affairs in England, providing through successive monarchs a continuity of sovereign tenancy that has prevailed to the present day. King Harold`s defeat and death on that fateful day in 1066 signalled an abrupt end to any meaningful defence by the English nation against Norman rule. In Wales events during this period of history were of course very different. The stubborn resistance of the Welsh population to Anglo-Norman rule lasted several centuries, helping to preserve the national culture of Wales down to the present day, an identity whose ancient language and culture are acknowledged as being among the oldest in Europe.

Unfortunately, while history by and large portrays King Harold as being a brave defender of his country, when describing the prolonged Welsh resistance to Anglo-Norman rule in South Wales, the majority of historians are not so generous in their praise, with terms like `marauding war bands` or `hot-headed troublesome murderous rebels` regularly used to describe Welsh resistance to the foreign rule of their land. In this version of events, resistance is described as `savage revolts causing death and destruction`, which included vandalism against the churches of the ‘more enlightened’ Normans. All too often these sour descriptions of the medieval princes of South Wales have been perpetuated by historians down the ages up to our own times, where internet searches on the princes and lords of Afan will find comparisons to the Taliban and even references to the English nursery rhyme of` ’Ten Green Bottles`.

Although the Princes of North Wales, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (Llywelyn Fawr) and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf) are credited with organising a collective Welsh resistance against the Anglo-Normans, the contribution made by the princes of South Wales in defence of their country is sometimes overlooked. This resistance can be seen in the actions of the Princes/Lords of Afan, who over 200 years after the Normans defeated England were still actively opposing the occupation of their land in South Wales. During the 12th and 13th centuries the Afan district, or Afan Wallia, became the springboard for sporadic insurrection against the hated Anglo-Normans, who had established enclaves at nearby Swansea, Neath, Kenfig, Llangynwyd and Newcastle (Bridgend).

Unfortunately, all too often this resistance tends to be summed up as a negative footnote in this period of our history. The introduction of the curious French/Welsh hybrid name of `de Avene`, used about the 7th Lord of Afan, Leision ap Morgan Fychan as a new surname to identify the once princely family, is usually accompanied by terms such as `throwing in their lot with the English` or `they became vassals of the Normans`. While this may appear to be true (in fact Leision signed his 1307 charter as Leision ap Morgan, not de Avene, which was perhaps the Latin version of his title), the oversimplification of these descriptions of the last few decades of tenure of the Lords of Afan in the mid-14th century tends to greatly detract from the realities of the events that were unfolding at the time. Faced with the realities of life in the immediate aftermath of the failed attempt by Llywelyn the Last to secure an independent Wales, it was incumbent upon the Welsh leaders of succeeding generations to work alongside what was by now English rule to secure a better future for all.

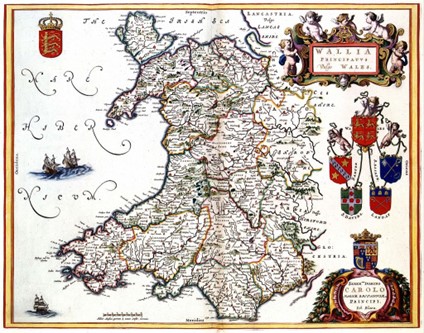

By Joan Blaeu – collections of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, National Library of the Netherlands., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41671507

Looked at in this context, the use of the title de Avene by Leision and his successors can be seen in a more positive light. In 1350, when Sir Thomas de Avene issued a new charter for the Afan district, he was able to do so from a position of relative strength. This strategy enabled the Welsh dynasty of Afan Wallia to at least continue to the last few decades of the 14th century, although as the 15th century Baglan poet Ieuan Gethin records in the following englyn, `the kingdom of Afan`, as he puts it, ended in 1318, a date that marked the execution of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Senghenydd, otherwise known as Llywelyn Bren, the leader of a revolt in 1316 against Edward II. The revolt failed, and Llywelyn Bren surrendered. At first he seemed likely to be pardoned, but then Hugh le Despenser seized him and had him executed in a particularly barbarous fashion.

“Mil tri chant gwarant gwirion – a deunaw

Fe dynnwyd yn gyfan

Gan drais mawr I lawr yn lan

Hynafiaeth Brenhinoedd Afan.” [8]

“One thousand three hundred and eighteen

When ceased

Through great violence

The ancient ancestral Kingdom of Afan” [8]

Ieuan Gethin`s 15th century reference to the `ancient kingdom of Afan` was touching upon the association through inheritance to the older kingdom of Morgannwg and Glywysing, an area we roughly associate today with Glamorgan and Gwent.[2] The English antiquarian John Leyland, on a visit to the Afan district in the 1530s seems to have been informed locally of the area`s past connection to Welsh royalty: referring to their ancestors as `Lysans` (Lleision), he wrote

“One Lysan, a gentleman of ancient stock, but now of mean lands, about a xl li by the year, dwelleth in the town of Neath. The Lysans say their family was there in fame afore the conquest of the Normans.”[3]

The last native ruler of this Welsh dominion was Iestyn ap Gwrgan, the father of the first Prince of Afan, Caradog ap Iestyn.

Unfortunately, Iestyn ap Gwrgan`s actual role in the invasion of South Wales by the Normans has been lost; a later account by Sir Edward Stradling, the legend of the Twelve Knights of Glamorgan, seriously confused matters and Iestyn`s eventual fate is unknown. The 16th century antiquarian Rhys Meyrick stated that having been defeated by the Normans, Iestyn took flight with his wife, eventually taking sanctuary at a place called St. Austin`s near Bristol. After residing there for a few years, they were both removed to Keynsham Abbey, where they died of old age and were buried in the Abbey grounds. However, Keynsham Abbey was not founded until much later, and as Meyrick collaborated with Sir Edward Stradling, creator of the story of the Twelve Knights, this version can only be marked `not proven`.[4]

King Hywel Dda Laws of Hywel Da from Peniarth MS 28 National Library of Wales, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

After Iestyn ap Gwrgan`s death the Normans apparently found it expedient to allow his eldest son Caradog to retain the territory between the rivers Afan and Nedd, which stretched from Hirwaun in the north to the sea at Aberafan and Baglan; the dominion of their rule became known as `Afan Wallia` (Welsh Afan). Caradog`s family were to exert a tremendous influence in the county and region of Glamorgan until the mid-14th century. His control extended over the whole of the Blaenau or mountain regions of Glamorgan, from Neath to the upper Taff. This area in turn was sub-divided into smaller lordships under the control of his younger brothers, and this clearly established Afan Wallia as being the headquarters of early Welsh resistance to the Anglo-Normans in South Wales. For several generations the descendants of Caradog resisted Norman rule, and Caradog`s son, Morgan ap Caradog was described as the “paramount ruler” of the hill country of Glamorgan in the twelfth century.` [5]

Mynydd Dinas seen from Port Talbot centre

Photo by Julian James

Even after the 14th century the direct descendants of the Princes/Lords of Afan continued to play an important role in the cultural and political affairs of South Wales from their base at Plas Baglan. It is known that this house became the haunt of famous Welsh poets such as Dafydd ap Gwilym (1320- 1370), who would have visited, and later Ieuan Gethin (c. 1385-1450), who lived within its walls. This shows how, like other great Welsh houses, the dynasty of Afan Wallia maintained a strong Welsh identity both during and after this period of encroaching feudal rule by the Anglo-Normans.

Ieuan Gethin, who resided at Plas Baglan, is particularly interesting in this context, as more is known of his life and work than of his predecessors. He is acknowledged as being the first of a new generation of bards known as cywyddwyr, which emerged in Morgannwg in the middle of the 15th century. In his youth he had the reputation of excelling in song and satirical expression which led to him being described as `A doughty fighter and a master of biting verse.’

His status as a gentleman freed him from the usual constraints of the paid bards, who were obliged to write more formal elegies of the period, and from his ten extant poems [6] we are able to glimpse a more personal portrayal of medieval life in South Wales. Alongside his skills as a poet, in his early twenties he, or possibly his father Ieuan Las is alleged to have been part of Owain Glyndwr`s struggle for Welsh independence, targeting the Anglo-Norman castles of Glamorgan.

Although this claim seems to have originated with Iolo Morganwg (who was an antiquarian, but also a romancer, so that it is difficult to be certain which of his stories is fact, not fiction), official confirmation of the fact appears to have been discovered in the Calendar of Patent Rolls, July 26, 1410.[7]

REFERENCES

1. DAVIES, L. Outlines of the History of the Afan District, The Author, 1914, p. 44

2. STEPHENS, M. ed The New Companion to the Literature of Wales, University of Wales Press, 1998, pp. 266, 511

3. SMITH, L.T. ed The Itinerary in Wales of John Leland in or about the years 1530-1539. George Bell and Son, 1906, p.36

4. STEPHENS, M. ed The Stradling Family in The New Companion to the Literature of Wales, University of Wales Press, 1998, p. 693

5. NEW, E. A. Lleision ap Morgan makes an Impression: seals and the study of medieval Wales, Welsh History Review, 26 (3), 2013, p. 342

6. OWEN, Ann Parry, `An audacious man of beautiful words`: Ieuan Gethin (c.1390-c. 1470)

in Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, 2014, p. 7 (Also see Chapter 7. `Ieuan Gethin and other poets at Plas Baglan`)