Princes of Afan

- Princes of Afan

- Chapter 1: Villains or Heroes?

- Chapter 2: Seals of Office

- Chapter 3: The Aberafan Charter, c.1306

- Chapter 4: Where they lived

- Chapter 5: Where They Worshipped

- Chapter 6: Other Local Sites Associated with the Afan Dynasty

- Chapter 7: Ieuan Gethin and Other Poets at Plas Baglan

- Chapter 8: Time Line of Events Relating to the Princes of Afan

- Chapter 9: Princes of Afan in the Wider Context

- Chapter 10: The End of the Dynasty at Aberafan

Chapter 10: The End of the Dynasty at Aberafan

Leisan ap Morgan Fychan is usually seen as the Lord of Afan who finally became assimilated to his overlords, adopting their customs and even their style of names. He is noted as Leisan de Avene (though this could merely be the Latin version of his name at a time when Latin was still the language of official documents. D`Avene would then be the logical sequel to this. His charter for the borough of Aberafan was issued under the name of Leisan ap Morgan). His wife is listed as Margaret (or Sibyl) de Sully – was it she rather than Leisan who chose John and Thomas as names for their sons? It was her ghost which was said to haunt the castle ruins, which suggests that she was a formidable figure.1

Earlier generations had married Welsh wives, but though the last four Princes of Afan and their children married Anglo-Normans – Turberville and de Barri for example – this was not unusual, and certainly no sign of the Welsh princes, of North or South Wales, rejecting their native ties. Leisan`s heir, Sir John, married Isabel de Barri and their son, Thomas married Maud, whose name suggests that she too was Anglo-Norman. The Turbervilles were said to have gained Coity by marriage with a Welsh heiress and Morgan Gam`s sister Mallt married Gilbert de Turberville. Llywelyn Fawr married King John`s daughter Joan.

Detail of Joan’s sarcophagus in St Mary’s and St Nicholas’s Church, Beaumaris

Llywelyn2000, CC BY-SA 4.0

via Wikimedia Commons

Perhaps because this was so often a union between a Welsh prince and an Anglo-Norman wife, its relevance has not been properly noted – wives tend to be left off the pedigrees – but this kind of intermarriage was characteristic of the Marches, of which Afan was in many ways an extension, and does not, as is often suggested, mean that either side became some sort of medieval collaborator. Leisan`s sons were John and Thomas, but Thomas`s sons were another Thomas and Morgan, while somewhere in there was another Leisan, so that the adoption of English names was seemingly temporary. Other branches, like that of Ieuan Gethin at Plas Baglan, continued to use Welsh names.

The Avene Coat of Arms

Courtesy of Paul R Davis

Leisan de Avene issued his charter c. 1304 and his grandson Thomas issued a confirmatory charter in 1349.There are a few references after that, but these end c.1359. The next, rather different, charter was issued in 1373 by Edward Despenser, the successor of the de Clares as Lord of Glamorgan.2 The Afan family were still firmly ensconced in the area, but the lordship had gone. The traditional account as to how this happened says that Thomas, the last lord of Afan, had only a daughter, Jane, as his heir; she married Sir William Blount and the couple then exchanged their lands in Wales for Despenser lands in England and moved away to their new home.3 However, there is no surviving documentation for this, and Leslie Evans in his account of the Lords of Afan makes a rather different suggestion. He found that one Leisan d`Avene had been `granted the rents of the manor of Winderton in Brailes parish, Warwickshire, for life in recompense for 100 marks worth of land in Wales which Edward [Despenser] had from the said Leysant`. The trustees of Winderton manor were ordered to pay this to Leisan as an annuity of ten marks a year. Later Evans found what he assumed was the same Leisan acting as a tax collector in Lincolnshire, and then having the reversion of the manor of Frithby in Leicestershire after the death of Lady Mary Belers. Admittedly, the title of tax collector could be deceptive – the sheriffs of counties were tax collectors, but they employed a staff to do the actual collecting; still, it has to be said that an annuity of ten marks a year and the reversion of a manor hardly sound like reasonable compensation for the lordship of Afan.

In fact it may be possible to link the two accounts. In 1340, although Sir John d`Avene was apparently still alive, the title deeds of his estates were passed over to his brother Thomas, who then passed them on to Sir Robert de Penrice for safe keeping. Sir Robert then issued a deed listing the documents he had received, but not giving any details as to what they were. One of these was an indenture of covenants made between Leisan de Avene and Sir Thomas Blount. And though we do not know what the purpose or content of the covenant was, it does show that there was a connection between the two families. 4

This was the era of the Hundred Years War and so next, in 1373, we find one Leisan de Avene as part of Despenser`s retinue when the latter joined John of Gaunt and the Black Prince on their journey to France in an attempt to relieve Aquitaine. 5 Leisan was one of three Welsh esquires and 49 archers who joined Despenser, out of a retinue pf 599 men. (An esquire was next in rank below a knight. A few years later Owain Glyndwr also fought in a royal army as an esquire.) Although only three of the esquires could be identified by their names as Welsh, there were also a number of the Anglo-Norman gentry of Glamorgan in Despenser`s train: Stradling, St. John, Berkerolles and others. By now intermarriage here, and in the Marches generally, had created a new, though in some ways unrecognised, kind of social grouping, so that Leisan would most likely have felt he was among his fellows, not a stranger in a foreign army. In 1376 Leisan was at Calais (then an English enclave) and he and one John Martyn jointly received a war payment of £100 pounds for their services there; Martyn, who came originally from Northamptonshire, was at Calais for over twenty years. Among the leading figures in the English army was Sir Walter Blount, and though there is no specific reference to Sir Walter as connected with Calais , his two eldest sons and a grandson were closely associated with the town as its governor and as two of its treasurers. How significant this might be is unclear at the moment, but it is worth noting.

It has been assumed in the past, by Leslie Evans and others, that because there is no definite record of an Avene/ Blount marriage, this Leisan was the son and heir of Thomas d`Avene and that he handed over his inheritance in return for estates in England, but this seems unlikely. There are no documents giving the precise size of the Afan lordship, and certainly some of it had been handed over in the past, not least to Margam Abbey, but in 1349 Sit John d`Avene had three knight`s fees in Afan Wallia. A knight`s fee was the amount of land sufficient to support the knight himself, his family and his servants, and to allow him to procure arms and equipment for himself and his retinue if required to fight for his lord. Roughly speaking this was equivalent to a manor – between 1000 and 5000 acres, depending on the yield of the land. An inquisitio post mortem in 1349 had said that Sir John`s holdings were valued at £40 yearly; Leisan was said to have exchanged 100 marks` worth of land for his annuity of 10 marks (£6/13/4); if the annual value of the holdings was £40, then Leisan had made a very poor bargain. And why would he want to exchange a position of some importance for a post as a tax collector, even if that was not as basic as it sounds.6

If Thomas d`Avene`s heir was, as tradition and some pedigrees stated, a girl, Jane, who was still unmarried when her father died, then her wardship and marriage would have fallen to Despenser to decide; a marriage to one of the Blount family would not have disparaged her, and her Blount husband would no doubt have been happy to exchange Afan Wallia for estates closer to home. (A Sir George Blount of Shropshire later claimed to be descended from this Blount-d`Avene marriage.)7 As for Leisan, perhaps Thomas`s nephew or cousin, acquiring his parcel of land would have neatly rounded off Despenser`s new acquisition, leaving Leisan free to seek a more exciting career in the French wars. Earlier. Sir John had exchanged his manor of Sully for Briton Ferry, a similar exchange, consolidating his estates.

PRINCES OF AFAN: The Continuing Story

It is unlikely that we will ever know exactly how the lordship came to an end, but that did not mean the last of the family in the district or beyond. If the senior line had ended without a valid heir, there were still numerous junior branches, who had married into the local gentry and produced heirs of their own. These flourished, and have continued to do so, making their mark in the political, industrial and cultural history of Wales. One branch in particular, that of Rhys ap Morgan Fychan, brother of Leisan d`Avene, is specially noted for its contribution.8 Whether the Princes of Afan had had any earlier residence at Baglan is not clear; it is recorded in an Extent of the county made in 1262 that Morgan Fychan held half a commote in Baglan and Plas Baglan is at the moment dated c. late twelfth/early thirteenth century; only a detailed archaeological survey could reveal its early history in any detail. In any case Rhys ap Morgan Fychan took up residence in Plas Baglan; if the earlier date is correct, then he was not the builder of the Plas. At least four families of distinction were to be descended from him: the Thomases, later Llewellyns, of Baglan Hall; the Evanses of Briton Ferry; the Evanses, later Mackworths, of the Gnoll and the Williamses of Aberpergwm; the Williamses of Blaen Baglan were also descendants of Rhys, and made their mark locally. The two most often quoted of these descendants were Ieuan Gethin and the Williamses of Aberpergwm.

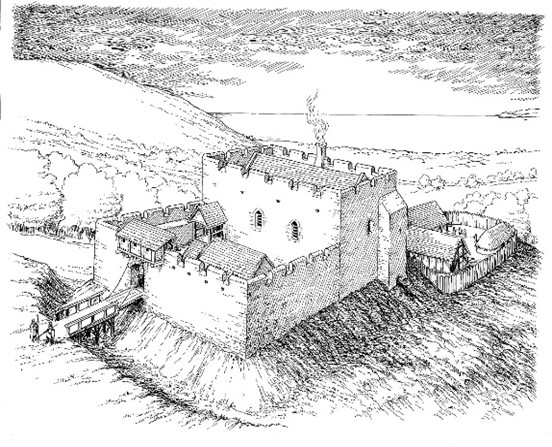

A suggested reconstruction of Plas Baglan seen from the north, by Paul R Davis

(from Towers of Defiance Y Lolfa 2021).

Ieuan Gethin was Rhys`s great grandson, the heir of Plas Baglan, remembered for his poetry.9 Happily enough of this has survived to show his skill and the range of his subject matter, from humorous commentary on life to deeply felt elegies on several of his children, who had died of the plague. He was not only a poet himself, but also a patron of the bards, holding open house for them at Plas Baglan, and poems in his praise by two other poets, Ieuan Du and Iorwerth Fynglwyd, have survived. The dates given for his life are various – 1405–1464, 1437-1490. fl. 1450. However Iolo Morganwg claimed that he was involved in the Glyndwr rising, which was finally over by 1415. Possibly Iolo was led astray by Ieuan`s poem in praise of Owen Tudur, grandfather of King Henry VII, but there is a reference to Ieuan Gethin and his wife being given a pardon in 1410 in terms that suggest they had indeed been part of Glyndwr`s campaign. Certainly one of the poets who wrote in his praise said that he was a noteworthy warrior. However, If Ieuan Gethin took any part in this campaign or in the Wars of the Roses – hence his interest in Owen Tudur – there is so far no definite evidence of this.

It is not clear who followed Ieuan Gethin at Plas Baglan. The Welsh pedigrees give his heir as William, but there is no evidence of him at Baglan and his name is not given in Ieuan`s elegy to his children; his younger brother Thomas held land near Cornelly. It was Eva, listed sometimes as Ieuan`s sister, sometimes as his daughter, who carried on the line at Baglan.10 She had married David ap Hopkin of Ynysdawe, also a descendant of the Afan family, and their third son,, John ap David, was the ancestor of the Thomases of Plas Baglan and later of Baglan Hall, to which the family moved in the later sixteenth century. In the later seventeenth century a member of the family, Robert Thomas, was one of the early Nonconformists, acting as pastor of a mixed group of Independents and Baptists, who were licensed to meet at Baglan Hall, It was Robert`s son and heir Anthony who wrote the description of Baglan parish for Edward Lhuyd`s Parochialia; the account is not lengthy, but full of fascinating detail about the area, including one of the earliest accounts of the dangers of coal mining. In the middle of the eighteenth century the male Thomas line came to an end, but the lineage was carried on by daughters, until in 1794 Catharine Jones married Griffith Llewellyn, himself also a descendant of Morgan Fychan, Lord of Afan. The family finally left Baglan Hall on the death of Mrs. Harriet Llewellyn in 1952, and the Hall was demolished in 1958, but the ruins of Plas Baglan still remain to bear witness.11

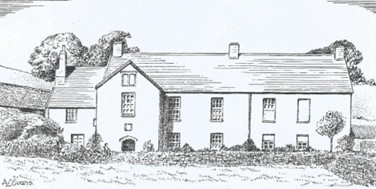

Baglan Hall

Courtesy of the Port Talbot Historical Society

It was Ieuan Gethin`s brother, Hopkin ap Evan, who was the ancestor of both the Williamses of Blaen Baglan and the Williamses of Aberpergwm. His great-great-grandson William ap Jenkin held Blaen Baglan and passed it to his son George, who took the surname of Williams, as did his brother Jenkin, who inherited his father`s interest in Aberpergwm and settled there. It was George who was responsible for building the house at Blaen Baglan; although in later centuries it functioned simply as a farmhouse, the Tudor building was a substantial gentry house, not unlike Llancaiach Fawr, though of only two storeys, not three.

Sketch of Blaen Baglan

A.L. Evans Copyright WGRO

George Williams is possibly the most noteworthy of this branch of the family. 12 He carried on the family tradition of patronage of music and literature, and was steward of the manors of Afan and Afan Wallia, and also Constable of Aberafan Castle. Lewis Dwnn describes him as a giant in war, though where or how he earned that title is not known. He certainly had a reputation as a litigious and warlike neighbour locally, appearing before the Star Chamber in London twice in 1584, in connection with a wreck at Aberafan which was claimed by both the Earl of Pembroke and Sir Edward Mamsel of Margam, and also with an attack on him by a number of local men. His tomb, a fine monument not unlike those of the Mansels at Margam Abbey, though lacking a figure of George and his wife, is in St,. Michael`s Church, Cwmafan. His line came to an end in 1691, after which Blaen Baglan was the home of a series of farmers, but after 1956 it remained untenanted. Sadly it is now a ruin in danger of collapse.

Blaen Baglan Farm in 2012 Photo by Tim Rees

George`s father, William ap Jenkin, had leased a farm and tithes at Aberpergwm from Leison Thomas, late abbot of Neath, and he left this to his second son, Jenkin, who established his family there, probably about 1560. 13 Successive generations regularly fulfilled their civic duties as members of the local gentry and were patrons of the bards; Dafydd Nicholas (1705-1774), though employed as a tutor to the household, was effectively the last household bard in Wales.

Portrait of Maria Jane Williams

National Library of Wales, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The best-known member of the family is Maria Jane Williams (1795-1873). She and her siblings had a good education, and Maria Jane played the harp and the guitar; she was associated with Cymreigyddion y Fenni, Lady Llanover`s circle, and won a prize at the 1838 Eisteddfod at Abergavenny for her pioneering collection of folk songs. She also had a collection of folk tales from the Vale of Neath published, and the authenticity of the material she collected was highly praised. Her brother William travelled widely and wrote poetry.

Engraving of Aberpergwm House, Glynneath, Wales. The History and Antiquities of Glamor-ganshire and its Families by Thomas Nicholas (1874), page 17.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Although the Williams family still own Aberpergwm House and estate, after WW2 it was leased to the National Coal Board, who used the house as offices and opened up mining operations in the park; eventually the house was left to fall to ruin.

Aberpergwm House 2010

Vouliagmeni, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Two other descendants of Rhys ap Morgan Fychan also founded local gentry families. William was the ancestor of the Prices of Ynysymaerdy, Briton Ferry. and his descendants duly filled their position as leaders of the county, serving as magistrates, sheriffs and MPs.14 Eventually they ended in an heiress, Jane, who married into the Mansel family of Margam. Her son Bussy was a notable supporter of Parliament in the Civil Wars of the seventeenth century. However Bussy`s son, Thomas, died without an heir and left his estate to his godson, another Bussy, who became Lord Mansel of Margam. Unfortunately the main Margam estate was entailed on the male line, and Bussy only had a daughter; she left the Briton Ferry estate, which was not entailed, to the son of a friend, William Villiers, who also died without heirs, so that it became the property of his brother, the Earl of Jersey.

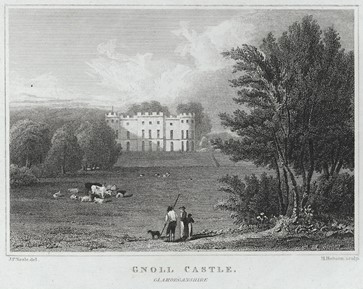

The Evanses of the Gnoll were also descendants of Rhys ap Morgan Fychan.15 They settled in Neath town, though they also held land at the Gnoll. David ap Evan, great-great grandson of Rhys ap Morgan, was a salt merchant – salt in those days before refrigeration was a major commodity. He was disenfranchised at one point for being involved in a protest. His son David, who took the surname of Evans, followed a career in the law and was the second native of Glamorgan to be elected as an MP. At that point the family lived in the Great House in Neath town; when the first house at the Gnoll was built is nor clear – apparently in the mid seventeenth century, but pictures of the town show an Elizabethan style house in front of the later Mackworth mansion, Later, as happened so often in the eighteenth century, the Evans line ended in a girl, Mary, who married Sir Humphrey Mackworth, The ultimate Evans-Mackworth heir died in 1794, but the house continued to exist until it was demolished after the Second World War; happily the grounds, landscaped by the Mackworths, are now a public park.

Gnoll Castle, Glamorganshire, by Neale, John Preston, 1780-1847 Hobson, H., fl. 1810, engraver.

Welsh Landscape Collection, National Library of Wales, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Although these lines often ended in childless marriages, the descendants of Caradoc ap Iestyn and his brothers were so fertile that there are more than a few still around, and often playing a leading role in Wales and the world. R.D. Blackmore, so often seen as the archetypal West Country figure, was a descendant through the Lougher family and launched his career as writer and horticulturist through the sale of land in Aberafan that he inherited from his uncle, Henry Hey Knight, vicar of Neath. 16 Rhodri Morgan, First Minister of Wales and his brother, the historian Prys Morgan are also Lougher descendants, and if the suggestion is also confirmed that the Powells of Carreg Cennen are descendants, then William Wilkins, one of those responsible for the establishment of the National Botanic Garden and the rescue of Aberglasney mansion can be added to the roll of honour.

REFERENCES

1. EVANS, A.L. The Lords of Afan in Transactions of the Port Talbot Historical Society, Vol. II, No. 3, 1974, p. 31

JONES, J.T, The Charters of Afan in Transactions of the Aberavo and Margam District Historical Society, 1928, pp. 45-6

2. O`BRIEN, J, Old Afan and Margam, The Author, 1926, pp. 70-78 (But see also, Dulley, A. The Aberafan Charter, c.1306.,above.)

3. EVANS, A. L. The Lords of Afan, pp. 38-30

4. EVANS, A. L., The Lords of Afan, p.36

5. CHAPMAN, Adam, Welsh Soldiers in the Later Middle Ages, 1282-1422, Boydell and Brewer, 2015 p.84

6. EVANS, A.L. The Lords of Afan, p.36

7. EVANS, A.L. The Lords of Afan, pp. 36, 38, 21

8. EVANS. A.L. The Story of Baglan, The Author, 1970, pp. 27-8

9. EVANS, Baglan, pp. 28-32

OWEN, Ann Parry. `An audacious man of beautiful words`: Ieuan Gethin (c. 1390-1470)

in Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 2014, pp. 1-39

10. EVANS, Baglan, pp. 35-38. Also see OWEN, Ann Parry, above

11. EVANS, Baglan, pp 32-54

12. EVANS, Baglan, pp. 55-64

PHILLIPS, D, Rhys, The History of the Vale of Neath, The Author, 1926, pp. 391-2

13. PHILLIPS, D. R. pp. 464-374

14. PHILLIPS, D.R. pp. 382-301

15. PHILLIPS, D, R. pp. 374-380

16. JONES, S. R.D. Blackmore and Glamorgan in Transactions of the Port Talbot Historical Society. Vol/ III, No.3, 1984, pp. 97-101