Princes of Afan

- Princes of Afan

- Chapter 1: Villains or Heroes?

- Chapter 2: Seals of Office

- Chapter 3: The Aberafan Charter, c.1306

- Chapter 4: Where they lived

- Chapter 5: Where They Worshipped

- Chapter 6: Other Local Sites Associated with the Afan Dynasty

- Chapter 7: Ieuan Gethin and Other Poets at Plas Baglan

- Chapter 8: Time Line of Events Relating to the Princes of Afan

- Chapter 9: Princes of Afan in the Wider Context

- Chapter 10: The End of the Dynasty at Aberafan

Chapter 4: Where They Lived

`Their country is fortified by nature.`

`In Wales no one begs. Everyone`s home is open to all, for to the Welsh generosity and hospitality are the greatest of all virtues. They very much enjoy welcoming others to their homes …`1

(Gerald of Wales, describing the typical Welsh home in the 12th century)

The general assumption is that when the Normans invaded South Wales the local Welsh population took to the hills, where they remained in relative safety from attack, abandoning whatever homes they occupied on the coastal plains prior to and during the invasion. The term used to describe their new imposed territory was the `Blaenau`, or the mountains, which obviously offered a more restrictive lifestyle, with less fertile land to sustain a day-to-day existence. Wherever there was a sizeable concentration of Welsh people the Normans used the term Wallia to describe the area, hence Afan Wallia for the area in which the indigenous people of the Afan district resided. Without the existence of the Princes of Afan the Welsh population that survived here would have been denuded of all rights and privileges, being forced to occupy the blaenau region, with little choice but to fight or accept owing fealty to their new masters.

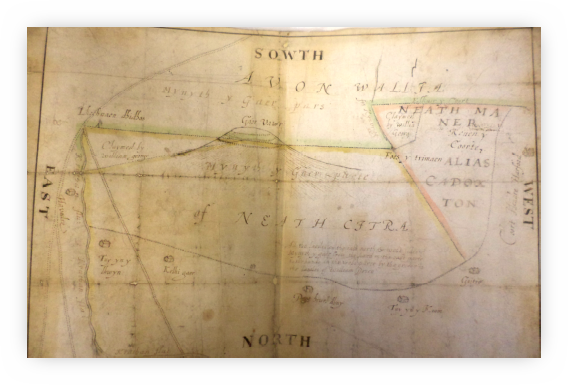

Map of Afan Wallia circa 1700.

West Glamorgan Archives Swansea {ref WGRO D/D BF E/1/12}

This early map from the West Glamorgan Archives (c. 1780) depicts part of the ancient south-west boundary line that existed between Afan Wallia and the Norman enclave known as Neath Citra, focused around the Iron Age hill fort on top of Mynydd y Gaer, the hill that overlooks Cwmafan and Baglan.

The territory of Afan Wallia was the only Welsh-occupied area in South Wales with access to the sea, with all the advantages that gave, not to mention a more pleasant sunnier climate, free from the shadows of the valleys. The gently sloping summit of Mynydd Dinas, with its plethora of natural water springs, towering 800 feet above the coastal landscape of Aberafan and Baglan, offered a formidable natural asset to the Princes of Afan, enabling them to develop a stable protected community whilst benefiting from its proximity to the coast. Today the name of the mountain, Mynydd Dinas, seems odd, because in modern Welsh `dinas` means `city`, but in earlier centuries it could have referred to a hill fort, as in Dinas Mawddwy or Dinas Emrys; another suggestion is that it was Mynydd Danas, or `Red Deer Mountain`.2

Despite afforestation, today Mynydd Dinas has many areas which have remained relatively untouched since medieval times. Walking the mountain to identify its topography and basic field archaeology offers us an opportunity to better understand how the land was utilized in the past, particularly when done alongside a study of historical documents and maps associated with the mountain, including the field names recorded in estate and tithe maps.

Today we can still see cattle grazing on the upper slopes of the mountain as they have done since the Middle Ages, and it is well documented that during the 13th century the Princes of Afan gave the monks from Margam permission to graze their cattle on Mynydd Dinas. On one occasion this invitation was extended to the lay brothers from Neath Abbey, which appears to have caused the Welsh princes a spot of bother, described in the following version of these events:

In 1175 Morgan ap Caradog granted Margam Abbey the exclusive rights to allow livestock to graze on common pasture on his land between the rivers Afan and Neath with the added promise that he would not allow any other religious men the same rights. This promise lasted until 1205 when, short of money, or as it was put in one of the charters, `Overcome with avarice`, he sold the same pasture rights to the monks at Neath for a period of two years.

This led to a bitter feud between the two abbeys with the monks from Margam driving the cattle off the land, which in turn led to the Neath monks employing a band of Welsh warriors on horseback, who were responsible for attacking and wounding the lay brethren from Margam Abbey as well as rustling the cattle they were looking after. Subsequently in 1208 a commission was set up in a bid to resolve the issues surrounding pasture rights between the two religious houses, resulting in Margam Abbey being granted two-thirds of the pastureland nearest to them, located in the mountains between the rivers Neath and Afan, while Neath Abbey was granted a third of the pastureland nearest to it.3

Evidence of former habitation on Mynydd Dinas from this medieval period can be found in the remains of several platform sites and fortified structures possibly associated with the Princes of Afan. In his contribution to Edward Lhuyd`s Parochialia in 1700, Anthony Thomas of Baglan Hall, himself a descendant of the Princes, comments on a group of three `castles`, two in Baglan and one in Margam parish, said to have belonged to three sisters, giantesses. That to the west was Castell y Wiriones (‘the foolish woman`s castle’); next, to the east, was Y Castell, and the third, in Margam, was Pen y Castell. These have also sometimes been linked with the Princes of Afan, but are probably very much earlier.4

(Princely and royal households in earlier centuries would have a number of residences, partly to enable them to travel round their territory and deal with its various problems, but also because the primitive sanitation of the period meant that each building would need to be thoroughly cleaned every few months, during which process the household moved elsewhere.)

Ruin of Margam Abbey Chapter House

Credit: Archangel12 via Wikimedia Commons

PLAS BAGLAN:

“A rare Welsh stone castle of the 12th century” 5

“An ancient house standing in the parish of Baglan, where Ieuan Gethin ap Ieuan ap Leision dwelt` 6

– Comment recorded by the English antiquary John Leyland, visiting the Afan district in the 1530s.

Located in a secretive, private wooded location, the importance of Plas Baglan as possibly the principal seat of the Princes of Afan is a recent suggestion, put forward, among other accounts, in the 1980s report on this site compiled by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. This proposes that it is more likely that Aberavon castle, previously held to be the administrative centre of the lordship, was only used by the Lords of Afan after 1304 when the first known charter for the town was issued. Earlier, the now vanished castle at Aberafan, near St. Mary`s Church, was always assumed to have been built by the Princes of Afan and used as their centre of administration. However, the only early reference to this castle, in Brut y Tywysogion in 1153, says it was destroyed by Rhys and Maredudd of Deheubarth, who were the uncles of Morgan ap Caradog, then Lord of Afan, and so it has come to be proposed that it was originally a Norman castle and the centre of princely administration was Plas Baglan. Whatever the truth of that (and see later, under Aberafan Castle), Plas Baglan was undoubtedly a site of importance, and in later centuries it was the family from there that carried on the inheritance of the Princes after the main line had come to an end.

If Plas Baglan and not Aberafan was the principal seat of the Princes of Afan for most of the 12th and 13th centuries, when they were engaged in major hostilities against the Anglo-Normans, questions are raised about the importance of the building and its surrounding countryside on Mynydd Dinas. Commenting in the 12th century as to why there were so few Welsh castles built during this period, Gerald of Wales comments

“Their country is fortified by nature` and `their secret strongholds lie deep in the woods.” 7

Gerald and Morgan ap Caradog were second cousins (their grandparents were brother and sister) so if the castle was in being by 1188, it is not too far-fetched to believe that he was thinking of sites like Plas Baglan when he recorded that observation.

Another contemporary account from an English perspective describes the Welsh as being `Wild men from the woods` 8, suggesting their reliance on using the cover of woodland and hilltops, and their intimate knowledge of the forests and mountains, using the natural landscape to build a defensive system out of sight of their enemies. Pitched battles were rarely successes for the Welsh; guerrilla warfare was their strong point, as even Julius Caesar had had to admit with regard to their Celtic ancestors.

The name ‘plas’ in Welsh means large mansion, which, along with its later association with the Welsh bards, has tended up till fairly recently to wrongly categorise Plas Baglan as being a dwelling house of the uchelwyr or upper class. However, since the 1980s the location has been identified as a fortified site, built in the 12th century, which possibly succeeded an earlier fortification built by Caradog ap Iestyn or his son, Morgan ap Caradog.

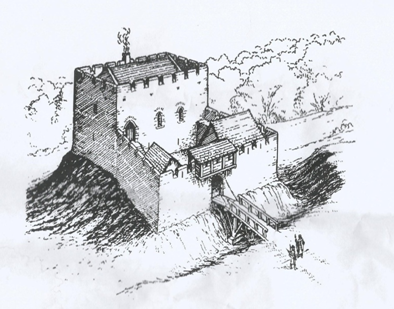

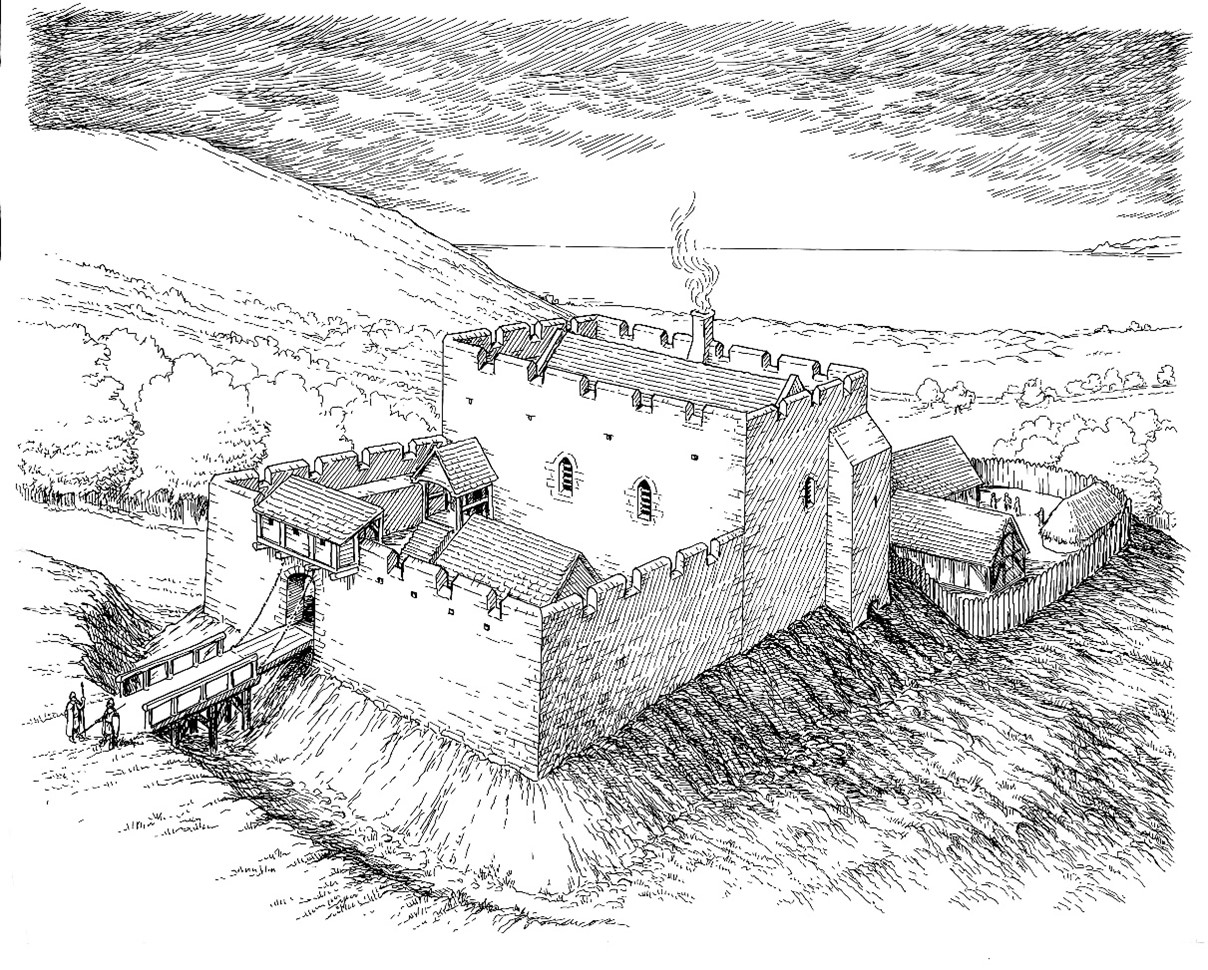

Below is a recent artist`s impression of Plas Baglan, along with an aerial plan of the building, showing its defensive embankments and outer bailey. Its location, on the eastern side of the very steep Cwm Nant Baglan, offered a formidable natural defensive feature to its builders, taking advantage of two small steep-sided valleys either side of the site, and making access for any attackers very difficult.

Drawing of reconstruction of Plas Baglan by Paul R. Davis (from ‘Castles of the Welsh Princes’ Y Lolfa 2007)

On the immediate western side of this steep ravine a study of earlier tithe maps and associated field names linked to the area reveals two fields known as Gadlish Fach and Gadlish Isaf, which translate as `the small battle court` and `the lower battle court`. These field names raise intriguing questions: may there have been a forgotten battle that once took place there, perhaps between the Normans and the local Welsh population? Or could these names denote muster points for local troops to prepare for skirmishes, in particular attacks on Neath castle by the Princes of Afan fighting as part of a larger Welsh militia?

The Normans were known to use rapidly built motte-style castles to subjugate an established Welsh population. These were roughly built earthworks and timber stockades, often later rebuilt in stone. They were often built in the aftermath of a victory in battle, adjacent to the centre of a local lord, to enable the Norman aggressor to claim the rights and privileges appertaining to that territory.

It is tempting to speculate on the circumstances unfolding in 12th century Baglan, and to imagine the activities that took place on the mountain prior to the building in stone, some of it beautifully worked in Norman style, of the structure we know today as Plas Baglan.

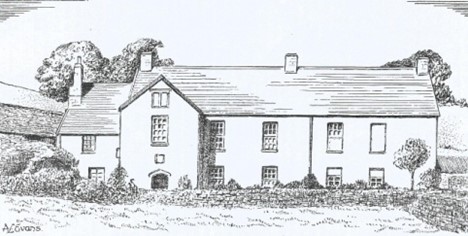

A suggested reconstruction of Plas Baglan seen from the north, by Paul R Davis

(from Towers of Defiance Y Lolfa 2021).

Early records of individuals and events linked to Plas Baglan are unfortunately non-existent, and its story as a defensive stronghold of the Princes of Afan will have to rely on the future work of skilled archaeologists if we are to understand the importance of this site. Apart from the mound it once sat on, and a few isolated blocks of Sutton stone, today there is nothing left to see of Plas Baglan.

The site of Plas Baglan today

Photo by Tim Rees

BAGLAN HALL AND BAGLAN HOUSE

Plas Baglan was abandoned as a principal family home in the early 1600s when a more commodious house, known as Baglan Hall, was built a little further to the west of the parish. Its later neighbour, Baglan House, built in 1760, is also shown below. Stones from the old Plas Baglan were believed to have been used in the construction of both Baglan Hall and House; despite its having been extensively altered in 1812, at least one type of mullioned window was observed within Baglan Hall before its demolition in 1958, perhaps a faint trace of its medieval predecessor.9

Baglan House

Baglan Hall prior to its demolition in 1958

Images courtesy of Port Talbot Historical Society

OTHER BUILDINGS IN THE WESTERN MYNYDD DINAS LANDSCAPE

Blaen Baglan Farm

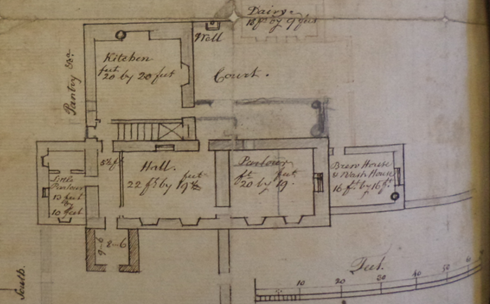

One of the other buildings in the near vicinity that benefited from the robust Sutton limestone of Plas Baglan was the Tudor house of Blaen Baglan. See below a drawing and plan from the Jersey Estate Archives in the West Glamorgan Archives of a building originally marked as ‘Unknown Building’, but which was identified by the author as an illustration of Blaen Baglan Farm.

From the Earl of Jersey Estate Records

By courtesy of West Glamorgan Archives, Swansea

A recent archaeology report on Mynydd Dinas Landscape 10 recognises this drawing to depict the house with its original square-headed windows, and details the presence of a dairy, well and brewhouse. It is described as ‘a substantial sub-medieval Glamorgan house’, first mentioned in 1566 when it was occupied by William ap Jenkin, a descendent of the original Afan dynasty. Rebuilt c1600 by his grandson William Williams, Blaen Baglan remained in the Williams family for most of the 17th century, until it was eventually acquired by the Jersey Estate by 1841.

Blaen Baglan Farm

Photo by courtesy of Port Talbot Historical Society

The BMA report quotes the RCAHMW, which is in turn informed by A. L Evans’ seminal report in 1965:

“The Williams family and the Thomas family of Betws shared a common ancestor in William ap Hopkin who was descended by a cadet line from the medieval lords of Baglan and ultimately from Iestyn ap Gwrgant.”

Sketch of Blaen Baglan

A.L. Evans Copyright WGRO

Blaen Baglan Farm in 2012

Photo by Tim Rees

Tŷ Newydd

Also part of this landscape, with possible connections to the original family, is an early 19th century farmhouse, Tŷ Newydd, now also a ruin.

Tŷ Newydd; date unknown

Photo by courtesy of Port Talbot Historical Society

Tŷ Newydd Farm still stood in the 1950s – see below some recent photographs showing the boundary walls of the now ruined farm. Note how the larger, robust square stones seem out of place with the rest of the wall structures.

Stones in wall of Tŷ Newydd

Photo by Tim Rees

The BMA archaeological survey of 2022 confirms this:

“Ty Newydd…features fan-tooled ashlar stone blocks originating from Plas Baglan which makes it an important associated site. In addition, the walkover survey identified three masonry bee bole or sheep creep niches with a distinctive herringbone construction.”

Plas Baglan is in the bottom of the field immediately to the left of the old farm site. It is possible that the 19th century farmhouse of Tŷ Newydd, given its name, occupied the site of an earlier medieval platform site, contemporary with Plas Baglan.11

Tŷ Newydd

E. Jones Baglan Then and Now A Pictorial Record The author 1988

Photo by courtesy of Port Talbot Historical Society

Site of long hut on Mynydd Dinas: one of many platform sites on the mountain

Photo by Paul R Davis

REFERENCES

1. Gerald of Wales: The Itinerary through Wales and the Description of Wales Penguin Books, 1978. p.236

2. JONES, A. B. Place Names of the Afan Valley, Goldleaf Publishing, 1988, p. 26

3. COWLEY, F. Neath versus Margam: some 13th century disputes in Transactions of the Port Talbot Historical Society, Vol.I, No 3, 1967, 00. pp. 7-9

4. PHILLIPS, M. and THOMAS, A. Aberavon and District about 1700 in Transactions of the Aberavon and Margam District Historical Society, 1931-2, p. 18

5. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Wales, Inventory of the Ancient Monuments of Glamorgan, Vol. 3, Part 1a), Early Castles 1991, pp. 149-152

6. TOULMIN SMITH, L. ed The Itinerary in Wales of John Leyland in or about the years 1530-1539, George Bell & Son, 1906, p. 36

7. GERALD OF WALES pp. 273, 268

8. CHILDS, W.R. Vita Edwardi Secundi, OUP (Clarendon Press), 2005

9. EVANS, A.L. The Story of Baglan, pp. 34-5

10. BLACK MOUNTAINS ARCHAEOLOGY Tirlun Mynydd Dinas Landscape Project Archaeological Appraisal Report 2022: BMA/2022/264, p.18

11. EVANS, A.L. The Story of Baglan, p.27