Princes of Afan

- Princes of Afan

- Chapter 1: Villains or Heroes?

- Chapter 2: Seals of Office

- Chapter 3: The Aberafan Charter, c.1306

- Chapter 4: Where they lived

- Chapter 5: Where They Worshipped

- Chapter 6: Other Local Sites Associated with the Afan Dynasty

- Chapter 7: Ieuan Gethin and Other Poets at Plas Baglan

- Chapter 8: Time Line of Events Relating to the Princes of Afan

- Chapter 9: Princes of Afan in the Wider Context

- Chapter 10: The End of the Dynasty at Aberafan

Chapter 5: Where They Worshipped

ST. BAGLAN`S CHURCH

A short distance from Plas Baglan, at the upper end of St. Catharine`s graveyard, is the ancient church of St. Baglan. Now a neglected ruin, it was formerly a centre of considerable importance.

St Baglan’s church: date unknown but before the fire

E. Jones’ ‘Baglan Then and Now: A Pictorial Record’

Photo Courtesy of Port Talbot Historical Society

Window in St Baglan Church. Photo: Tim Rees

The legend of St. Baglan

St. Baglan was a native of Brittany; he came to study at the monastery of Llanilltyd Fawr [Llantwit Major], which had become a distinguished centre of learning under the leadership of St. Illtyd (c. 490). One day St. Illtyd, who was feeling cold, sent Baglan to get some hot coals to start a fire. Baglan, not having anything to carry them with, put them in the skirt of his robe, and St. Illtyd was so impressed when he saw that the robe had not been scorched, that he sent Baglan off on a missionary journey. He told the young man to walk until he came to a tree that carried three kinds of fruit, and he gave him a staff (bagl) – from which the saint supposedly got his name. Baglan duly walked west, eventually sitting down to rest under a tree – which had a crows` nest at its top, a bees` nest half way down, and a litter of pigs at its foot. However the tree was on a slope and Baglan decided to build it on the flatter ground below, only to find that every night the day`s building was taken up to the higher ground. At last he gave in and the church was built where it still stands today.1

Originally the church at Baglan would have been Baglan`s own small oratory, with a well nearby, like St. Seiriol`s foundation at Penmon in Anglesey. Later a church was built, to accommodate the members of the parish, and that continued to serve the local people over the centuries. In the later Middle Ages Baglan was part of a much larger parish, based on St, Mary`s, Aberafan, and also including the chapelries of Llanfihangel Ynys Afan (Cwmafan) and Glyncorrwg, For two years after 1768 it even also served the parishioners of St. Mary`s, Aberafan, when that church was seriously damaged by flooding.2 Then, as Baglan`s population grew, the old church became too small and a new building, St. Catharine`s, was erected and consecrated in 1882. St. Baglan`s was used then for services in the Welsh language until it was gutted by fire in May 1954, leaving only the walls still standing.

St. Baglan`s Church

Interior of St Baglan’s church before the fire of 1954

From E. Jones’ ‘Baglan Then and Now A Pictorial Record’

Photo Courtesy of Port Talbot Historical Society

St Baglan’s church 2023

Photo by Tim Rees

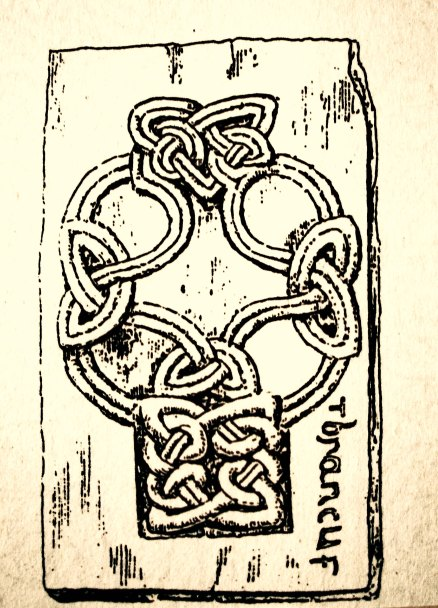

St Catharine`s houses the Brancu Stone, a memorial from the 9th or 10th century, carved with a wheel cross in low relief and the name BRANCU at one side. Another carved stone was found recently, buried in the grounds of the old church during restoration work to the graveyard. It has a basic Maltese cross and was probably a wayside cross, placed alongside a pilgrim route, a spot where a weary traveller could stop and pray. Such a cross is believed to have existed near an old stile on Baglan Road, near Sticyll Wen farm, offering the possibility of this being the same stone, perhaps relocated to the grounds of Baglan Church.

Brancu or Brancuf Stone.

Credit – ‘Lapidarium Walliae’ The early Inscribed and sculptured stones of Wales Prof J.O. Westwood. Printed at Oxford University Press, for the Cambrian Archaeological Association 1876 – 1879. Page 24

Stone with cross in Baglan Church graveyard.

Photo: Tim Rees

The double bell tower of St, Baglan`s is an unusual feature, and a recent survey of the old church in 2023, after it had been cleaned of creeping vines, uncovered an unusual image carved into a stone on the top right of the bell tower. It is thought that this may be the image of an eagle, a figure linked to St. John the Evangelist and the Fourth Gospel, and its lopsided position suggests that it may have been robbed from somewhere else.

The ruined twin tower of Baglan Church.

Photo by Tim Rees

The BMA report of 2022 quotes Cadw:

“The site forms an important element within the wider medieval landscape.”

St.Mary’s Church

The present St. Mary`s Church is a 19th century building, and almost nothing remains of its earlier incarnations. However, it will have begun as the garrison church of Aberafan Castle, and there are references to various chaplains and priests of Afan from 1199 onwards. Whether it was one of the buildings burnt down in the attack of 1153 is not known. The graveyard contains the base of the town cross.

There is some evidence, written, archaeological and traditional, that the original settlement here, in the early First Century, was at the mouth of the river Afan and nearer to the sea, but it was either besanded or destroyed by flooding.3 Then, at the beginning of the Twelfth century the Princes of Afan built a fortification at the crossing point of the river, on the main road to the west. Because they were on their home ground Welsh castles (cf Dolwyddelan in Eryri) were not grandiose like Caerffili, but they were sufficiently substantial, and they would have what we might call a garrison church nearby, in this case the original St. Mary`s. Aberafan Castle was certainly in being by 1153 when it was burnt down – this was a timber construction, but it was rebuilt in stone.

The first relevant reference is from 1199, when Wrgan, `the priest of Afan` put his signature to a grant of land by Morgan ap Caradoc. The early relationship between the castle and the church can be seen when in 1240 Gregory, witnessing one of Morgan Gam`s charters, is described as `chaplain of Afan`.4 The town of Aberafan would then have been very small indeed, very largely made up of the inhabitants of the castle, their servants and the various traders and craftsmen who provided services, and it was common sense for the castle chaplain to be also the rector of the parish church. (The church was reached by a drawbridge from the castle.) Because of the relationship between the Princes of Afan and Margam Abbey we have the names of some of these medieval rectors, for example Thomas, rector in 1350, who drew up the enlarged borough charter for Thomas de Avene and witnessed it. After the main line of the Princes of Afan died out in the 1360s, St. Mary`s was placed under the patronage of Margam Abbey and the borough became part of the lordship of Glamorgan.

Margam Abbey

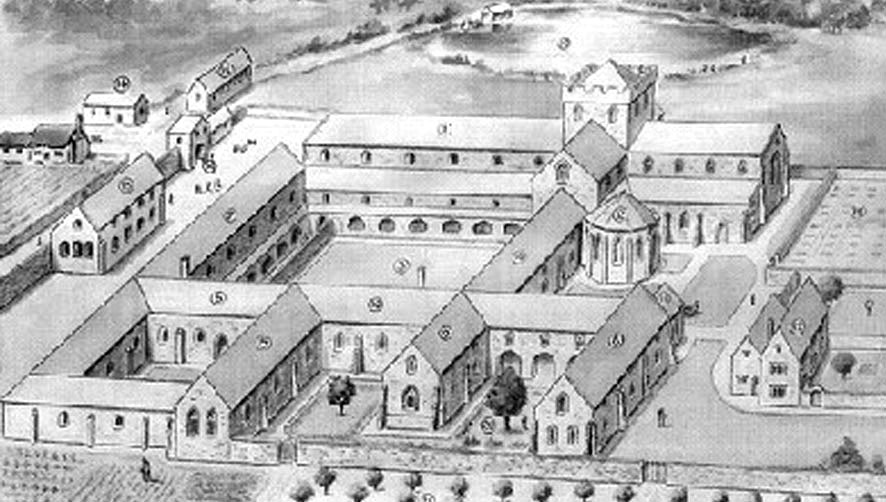

Although Margam Abbey was not a residence of the Princes of Afan, they were among its patrons, and many of them were buried there. The territory of Margam (or Margan as it was also called) was much larger than the modern parish of Margam, and was probably Owen ap Caradog`s share of the family inheritance. According to Gerald of Wales Owen was murdered by his brother Cadwallon, for unspecified reasons, and the land, including the so-called Tir Iarll (Earl`s Land) came to Robert of Gloucester. The land granted to the monks was that between the rivers Kenfig and Afan

“from the brow of the mountain, as the said rivers descend from the mountains to the sea, in wood and in plain; and my fisheries of Afan, for founding an abbey free and quit of all customs.”5

Robert is normally credited with being the founder of Margam Abbey, but it would clearly not have been possible to build it without at least the co-operation of Caradog ap Iestyn and his son Morgan ap Caradog; although the Princes or their tenants sometimes attacked the abbey granges (farms) as part of their military activities, they never harmed the abbey itself.

Reconstruction of Margam Abbey A.L. Evans – Margam Abbey.

Plate 4

A.L. Evans Copyright WGRO

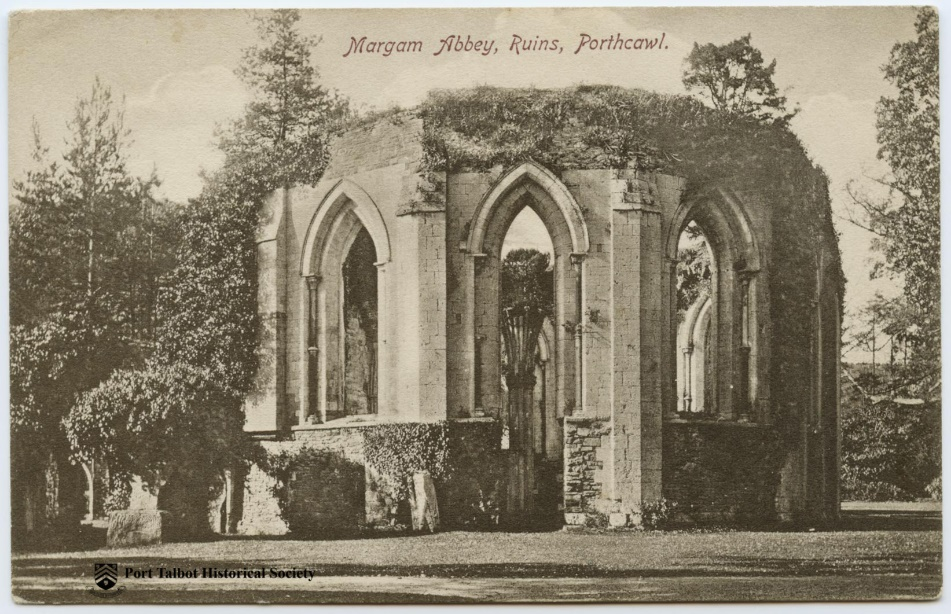

Chapter House ruins, Margam Abbey.

By courtesy of Port Talbot Historical Society

There were Benedictine foundations in Wales before the Cistercian monks arrived; for instance, Richard de Granville`s abbey at Neath was founded in 1129 for the Savignac order, though that merged with the Cistercians in 1147. The Cistercians came to South Wales c.1140. moving to Whitland in 1151; their founder was Rhys ap Gruffudd, who was also the founder of Talley Abbey. Strata Florida was founded by his cousin, Robert FitzStephen, son of Nest ferch Rhys ap Tewdwr. In medieval society marriages were usually political rather than romantic affairs, but that did not lessen their significance.

Long before the Normans appeared on the scene, Margam was apparently a Celtic religious centre. The evidence for this is the remarkable collection of Celtic inscribed memorial stones and crosses, including the Wheel Cross of Conbelin, found locally and now housed in the old school building next to the abbey, though the precise nature and location of such a centre has not been discovered. There has been speculation about the 14th century Capel Mair on the hill above Margam, but that awaits further research.

The medieval ruins of Capel Mair with Margam Mountain in the background.

Photo: Friends of Margam Park

The Great Wheel Cross of Conbelin, Margam

Robin Leicester, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The motivation of the Princes of Afan in this context are clearly stated through the wording of their charters linked to the new abbey. A 1205 charter of Morgan ap Caradog granted land to the abbey stipulating that:

“This is granted for the souls of his father and mother, and of all his ancestors, and for his own soul`s sake” 6

further adding that he be buried at Margam, a wish believed to have been granted three years later, after his passing.

Margam Abbey ruins, believed to be the burial place of Morgan ap Caradog and others of the Afan dynasty.

Credit: Archangel12 via Wikimedia Commons

Nominally religious foundations were set up for the benefit of the founder`s soul and that of his family, but Neath and Margam are interesting cases. Were they, as often said, intended to ensure that the Princes of Afan behaved, or were they possibly meant to protect the strategic area of Afan Wallia from being taken over by one of the more ambitious Norman barons who rather too often rebelled against the Crown?

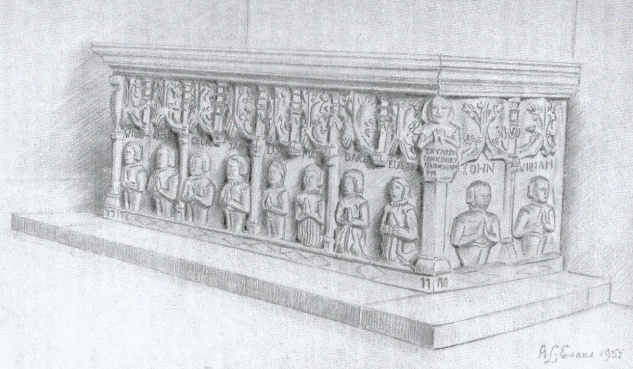

Although the two churches most associated with the Princes of Afan are St. Baglan`s church and St. Mary`s, Aberafan, St. Michael`s church in Cwmafan also has a link in the shape of the tomb of George Williams of Blaen Baglan, who was a descendant of a cadet branch of the family at Plas Baglan.7 The tomb is now used as an altar table and the figures on it represent George Williams (d. 1600), his wife Maud Lougher and their twelve children. The tomb bears the oldest Welsh language inscription in the district: “Y Trymped Pan Kenir Y Meirw Y Gofydyr”: “The trumpet shall sound at the rising of the dead.” 8

The tomb of George Williams of Blaen Baglan, in St Michael’s Church, Cwmafan.

Illustration from A.L. Evans ‘The Story of Baglan’

REFERENCES:

1.Phillips, Martin and Thomas, Anthony, Aberavon and District about 1700 in Transactions of the Aberavon and District Historical Society 1930, p. 47

2. O`Brien, James, Old Afan and Margam, The Author, 1926, p.61

3. Cadw, 2022, St Baglan’s Scheduled Monument Report http://cadwpublicapi.azurewebsites.net/reports/sam/FullReport?lang=en&id=3120, Accessed 16/10/22

4. O`Brien, James, Old Afan and Margam, p. 46-52

5. O`Brien, James, Old Afan and Margam, p. 65

6. Evans, A. L., Margam Abbey, The Author, 1958, p. 17

7. Birch, W. de G., A History of Margam Abbey, The Author, 1897, p. 159

8. Evans, A.L., The Story of Baglan, The Author, 1970, p. 58-60