Princes of Afan

- Princes of Afan

- Chapter 1: Villains or Heroes?

- Chapter 2: Seals of Office

- Chapter 3: The Aberafan Charter, c.1306

- Chapter 4: Where they lived

- Chapter 5: Where They Worshipped

- Chapter 6: Other Local Sites Associated with the Afan Dynasty

- Chapter 7: Ieuan Gethin and Other Poets at Plas Baglan

- Chapter 8: Time Line of Events Relating to the Princes of Afan

- Chapter 9: Princes of Afan in the Wider Context

- Chapter 10: The End of the Dynasty at Aberafan

Chapter 6: Other Local Sites Associated with the Afan Dynasty

Aberafan Castle

Although there are no contemporary records of the earliest history of Plas Baglan, we do have the remains of the fortified structure built c.1200 AD, presumably by Morgan ap Caradog. Whether the site was in use earlier is unknown, though an archaeological survey might reveal more. However, Aberafan Castle is an even greater enigma. The only record of its existence is a note in Brut y Tywysogion of its being attacked and destroyed by Rhys and Maredudd ap Gruffudd in 1153, and in recent years in particular this has led to some authorities suggesting that it was a Norman built and held castle, not a creation of the Princes of Afan, though they may later have taken it as their main residence.

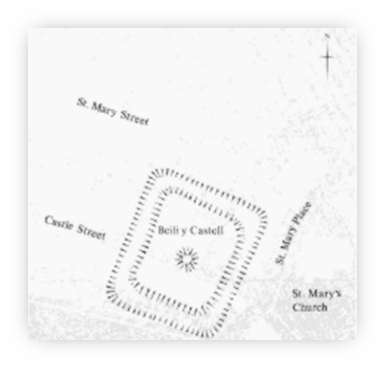

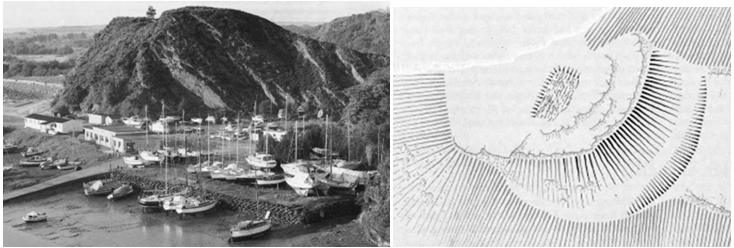

Fig. 109- Aberafan Castle: the location of vestiges recorded in 1876 on the O.S. 25-inch map

Glamorgan Early Castles RCHAMW p 155

The last visible remains of the castle lay just across the wall surrounding St. Mary`s church. They disappeared in 1895 with the building of several aptly named terraced streets – Castle Street, Bailey Street, St. Mary`s Place and St. Mary Street, and though there were rumours that a painting of the castle existed, none has come to light. The first edition of the 25 inch OS map of 1876 shows the remains of the castle as a large rectangular enclosure measuring 55 metres by 46 metres (160 x 140 feet) internally, with a surrounding ditch averaging 13.5 metres (39 feet) wide. There is a small circular feature in the centre of the rectangle; this might have been a motte, but it has also been suggested that it was a cockpit.1 The dimensions given suggest a structure much larger than Plas Baglan. Although the castle seems to have been left to decay after the main line of the Princes ended c. 1360, it continued to be a centre for the civic ceremonies of the town of Aberafan up until the later 19th century, and the Constable of the castle was one of the civic officials of the pre-1860 borough.2 One of the earliest descriptions of the castle was by an anonymous Welsh poet who composed the following verse about the ruins of Aberafan Castle:

Yma bu rhoddfa brydferth

Och weled ei chwalfa mor anferth

Cwympo a rhwygo yn rhygerth

Furiau wnaed yn fawr eu nerth.

Here there was a splendid walkway,

Sad to see such destruction

Now laid low in fragments.

These walls, once so strong

As noted above, the reference to the destruction of the original castle in 1153 has led some historians to suggest that the castle was a Norman garrison, since Rhys and Maredudd ap Gruffudd were brothers-in-law of Caradog ap Iestyn and uncles of Morgan ap Caradog, who was probably by then the current Prince of Afan, and there is nothing to suggest that this was a family quarrel. The reference in one manuscript of Brut y Tywysogion says that the attackers killed the garrison and made off with “immense spoil and innumerable riches”.3

The Peniarth version is a little different, and says

“After that, in the month of May, Maredudd and Rhys made for the castle of Aberafan, and after killing many and burning houses, they carried off with them vast booty.” 4

What is interesting here is the reference to houses, which suggests that Aberafan was a settlement, not just a stronghold as it might have been if the castle was a Norman garrison.

However, if one looks at the wider picture, a possible reason for the attack becomes clear. The Princes of Afan do not seem to have objected to the building of Margam Abbey, and in fact made grants of land to it and were buried there. Robert of Gloucester, the Abbey`s founder, died in 1147 and was succeeded by his son William. Although he built Cardiff castle, Robert inevitably spent much time away, in Normandy or fighting for his sister, the Empress Matilda, where William was more involved with his lands in Glamorgan. He seems to have been trying to extend his hold beyond its existing limits – for example he granted land on the border of Aberafan to one William Fitz Henry, who in turn granted land here to Tewkesbury Abbey. Though the date is not certain, this may also have been the period when William, having been angered by Morgan ap Caradog, had a hostage blinded in response. Then in 1158, William took land from the other major Welsh lord of the area, Ifor Bach of Senghennydd – who was, as it happened, father-in-law to both Morgan ap Caradog and William`s sister Mabilla. Ifor Bach took action, climbed into Cardiff Castle, seized William, his wife and his son and took them away into the woodland, keeping them there until William agreed to give the lands back. One might have expected Ifor Bach to have received some major penalty for this, but it seems that William had for once learned his lesson.

As noted earlier, the mention of houses being burned in 1153 shows that Aberafan town was already in existence. Although there have been suggestions by earlier writers that Caradog ap Iestyn issued a charter, the first that we now have dates from c. 1304/7 and was granted by Leision ap Morgan Fychan. It is short and a little misleading, since most of its grants relate to Leision`s `English burgesses and censers`; the censers were not, as previously thought, traders, but people, probably local, who also paid rents to the lord. It would seem that in order to promote the town Leison had encouraged merchants, perhaps from Bristol, to come to Aberafan, and he was giving them certain advantages in return. The charter also mentions the ordinances of Kenfig, and these were the basic bylaws about public order, regulation of trade, tolls, sanitation, etc which applied to everyone. We have no way of knowing how many English burgesses came, or, indeed, whether only Englishmen could be burgesses, which was the case in Norman founded towns. When we do finally, two hundred years later, get the names of the inhabitants, they are all solidly Welsh. 5

The castles of Norman settlement were at the centre of walled fortresses, and they kept the natives outside the walls, allowed in only during daylight hours. Much later on there is a reference in the records to town walls at Aberafan, but no evidence that anything more than perhaps a boundary hedge existed. Whether anyone lived in the castle once the Princes of Afan were no longer there is unknown, but it seems slowly to have fallen into ruins, though it was the focus of the annual civic ceremonies for another five centuries.

Legends linked to the Castle of Aberafan

Ladi Wen – the ghost of the White Lady of Aberafan Castle was a familiar story told amongst the inhabitants of Aberafan right up to the start of the 20th century. Her ghostly image could be seen hovering around the old castle site, near the graveyard of St. Mary`s church. She is believed to be either the ghost of Margaret, the mother of Sir John D`Avene, the 8th Lord of Afan Wallia, or his granddaughter Jane, who was believed to be the last member of the family to occupy the castle, leaving her ancestral home towards the end of the 14th century to marry an English knight, Sir William Blount in mysterious, now forgotten circumstances. The title Ladi Wen is believed to be a reference to the Virgin Mary, patroness of the church, the Welsh title meaning Holy or Blessed Lady.

Perhaps the most famous legend linked to Aberafan castle relates to an incident involving our very first prince of Afan Wallia, Caradog ap Iestyn. Being pursued by his enemies, he is said to have hidden in a mound near the castle. Whilst searching for him, his enemies noticed some doves lazily circling overhead near the mound, and not being able to find the Welsh prince, they left, concluding that had he been there he would have disturbed the doves. This lucky escape was captured in a magnificent large oil painting that once hung in the old municipal buildings, but has sadly disappeared, like so many of our ancient artefacts.

The last legend tells the story of Dafydd Ddu Grwydryn (Black David the Wanderer), a formidable warrior in the service of the Princes of Afan, who during an attack on Aberafan Castle stood his ground in the hall doorway, where he managed to slay eleven of the enemy attacking him. Not being content with this incredible feat, he the chased after two others who had fled, slaughtering them too.

Castell Bolan

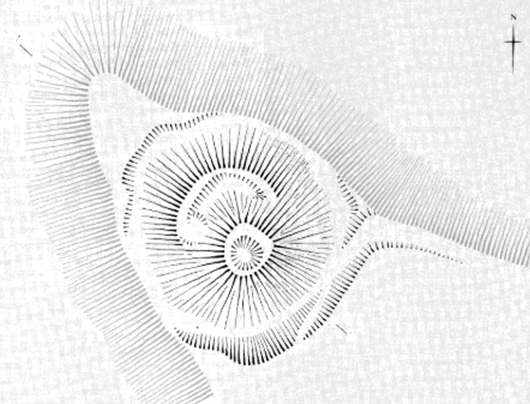

Now a ruin, described as a castle mound occupying a spur on the northern flank of Mynydd Dinas, its design appears to imitate a Norman motte type structure. This structure, a Scheduled Monument, known as Cwmclais Mound, or locally as Castell Bolan, is surrounded by defensive ditches. Its weakest point is on the eastern side, which faces out onto a large enclosed upland field known locally as Cae Mawr. Its use as a shooting practice area for a local 19th century defence group may well have partially destroyed its original earthworks. 7

Cwmclais Mound. Photo: Tim Rees

Plan of Cwmclais Mound, or Castell Bolan

Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales

This monument has not had any recent archaeological scrutiny and remains mysterious in terms of who built it, the Norman invaders or the indigenous Welsh. Indeed, in its probably short life in the hurly burly of the Norman piecemeal takeover of South Wales, it could have been controlled by both sides. This site would have been particularly useful in the 13th century when Morgan ap Caradog was allied with Llywelyn the Great to attack the Norman strongholds at Llangynwyd, Neath and Kenfig.

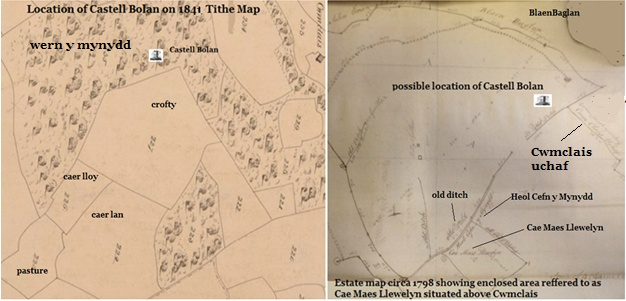

The area surrounding this monument also deserves some attention. The maps shown above, from 1798 and 1841, reveal some intriguing clues about the history of this site. A word of caution must accompany the estate map shown as correlating to Cae Mawr; although it has several features which seem to suggest it is the same area shown in the tithe map, there remains some doubt due to the lack of accurate detail on the estate map pinpointing its exact geographical location. The maps depict a large squared-off area of secluded elevated grassland directly in front of the Cwmclais mound fortification.

Comparison of tithe maps from 1798 & 1841.

Images by Tim Rees, courtesy of West Glamorgan Archives, Swansea.

However, if assumptions are correct and both maps are showing the same area known today as `Cae Mawr`, this area of land could warrant further investigation. Its regularised shape and its proximity to the castle remains could suggest that it is part of the medieval complex associated with Cwmclais Mound or Castell Bolan.

The breeding of large horses by the Welsh high nobility for military purposes in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries would have necessitated areas of suitable land close to their fortifications. Records indicate that some of the Welsh armies numbered more than 7,000, which included 800 mailed horsemen. The Princes of Afan, like other Welsh royal households during this period, would have maintained well-armed and mounted military forces; such activity would have required a local base from which to launch their attacks.

Given its close proximity and easy access to other Norman fortresses, such as Neath town and castle, via the Bwlch mountain pass, this castle in the heart of Afan Wallia, with its protected elevated field system on the eastern slopes of Mynydd Dinas, offers a plausible location for the mobilization of Welsh armies involved in the defence of their territory.

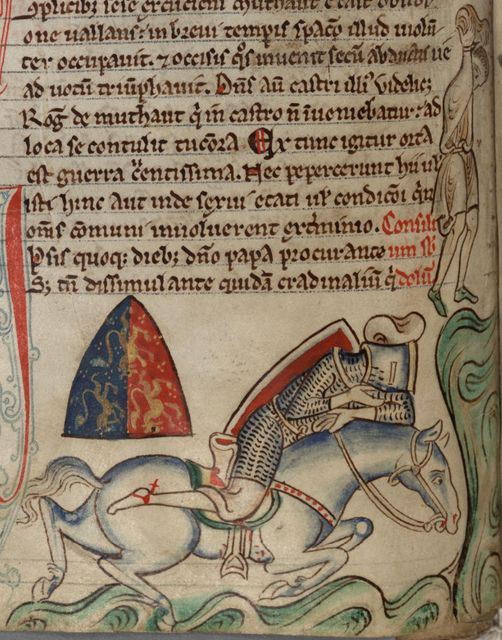

Additional evidence linking Nant y Clais to the military campaigns of the Princes of Afan can be found in Annales Cambriae (Welsh Annals). An entry in this document refers to a battle between Welsh and Anglo-Norman forces which is believed to have taken place in 1245 near Cwmclais, Cwmafan. The entry speaks of the death of a knight, Herbert Fitzmatthew, who was killed by a rock hurled at him by a Welsh fighter

`in quondam clivo prope castrum quod fuit Morgan Gam`

or

`on a hill slope near a castle which formerly belonged to Morgan Gam.’

The location has been identified by the local historian A. Leslie Evans as being on the slopes of Mynydd Dinas, near Cwmafan; this agrees with the chronicler Matthew Paris, a monk from St. Albans Abbey, who has included this in his Chronica Maiora.8

Painting by Matthew Paris 1245

Matthaei Paris Chronica Maiora II, The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College,

Cambridge MS 016ii, fol. 184v

https://parker.stanford.edu/parker/catalog/qt808nj0703

If we were to accept that this area was used as a military stronghold by the Princes of Afan, then the field name `Cae Maes Llywelyn` could bear some significance’ It is tempting to surmise a relationship with the Princes of Gwynedd, although there again caution should be applied to this notion, as there was a later member of this dynasty linked to the area, Griffith Llewellyn of Baglan Hall.

The name currently used for this site, Castell Bolan, is also of interest. I suspect this name is a relatively modern name due to the late 19th or early 20th century sources referring to its shape looking like a bowl or, in Welsh, `Powlen`. Locals I have spoken with, who worked on Cwmclais Farm in the early 1940s and 50s, say they remember the older workers referring to a nearby field being called `Cae Bowler` due to it resembling the shape of a hat. It is therefore possible that the name Bolan was mentioned by a local farm worker in an early archaeological survey by Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who we know studied remains on Mynydd Dinas in 1923, resulting in the name sticking.

Although the origin of the names goes back long before the time of Caradog ap Iestyn and his descendants, it is interesting to see how certain place names demonstrate the hold of Caradog`s family on the area even after the Norman invasion. Brynbryddan, a 1930s housing estate on the slopes of Mynydd y Gaer, is `the hill of the Britons`, probably taking its name from a Tudor farmhouse that once existed there. Briton Ferry is another such name – in 1188, when Gerald of Wales visited the area with the Archbishop of Canterbury, it was his cousin, Morgan ap Caradog, who escorted his party across the river Neath. Although Briton Ferry is a relatively modern translation, medieval chroniclers wrote of it as `passagium Briton`.

Painting of Brynbryddan Farmhouse c. 1897 in private ownership

Photo by Tim Rees

Hen Gastell

`One of the relatively few early medieval fortified sites in western Britain which became castles in the high medieval period.` 9

Hen Castell, on the west bank of the river Neath, and Warren Hill, an Iron Age hill fort opposite it on the east bank, are two lost castle sites, with the former being associated with the Princes of Afan, in particular Morgan ap Caradog, who is believed to have built the castle in 1183, when he and other princes were about to be involved in major battles against the Norman invasion of South Wales. Although it was only rediscovered in the 1980s, when work to build the new Briton Ferry M4 bridge started, earlier antiquarians, notably Rhys Meyrick [c.1520-87], who had read about it in the now lost Register of Neath Abbey, described it as laying on a steep hill near to the passage of Briton Ferry on the river Neath. It was evidently an important strategic location guarding the shipping route up the river Neath, as well as overlooking a treacherous ancient ferry crossing, known in 1289 as passagium de briton or Passagium aquae de Bruttone [1307], from which the Welsh could control the coastal route from Aberafan to Swansea and West Wales.

Hen Castell and its aerial plan as it looked prior to the extension of the M4 being built in the 1990s. The summit now underpins Junction 42 of the M4.

Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales

A famous incident occurred here in 1188 when Gerald of Wales on his travels around Wales recruiting for the crusades got stuck in the silted river bed, resulting in the near death of a horse and the loss of some of his precious books. 10

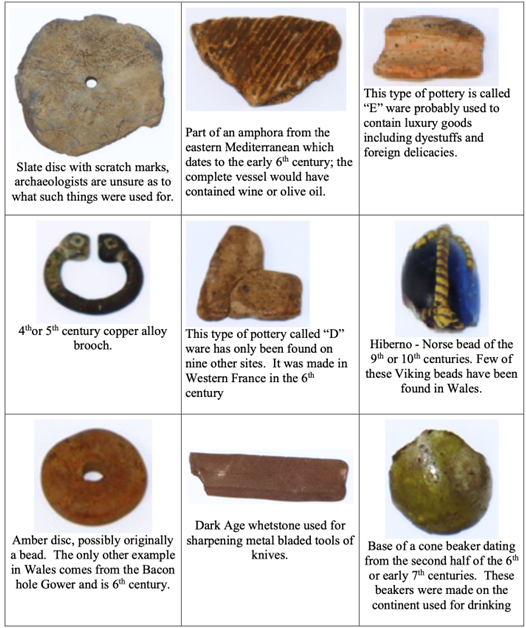

Archaeologists excavating here in 1991, as well as finding evidence supporting its use in the 12th century, were surprised to find items from a much earlier period, such as a high-class brooch, Mediterranean glass, string beads and pottery ware from the 5th century, along with 9th -10th century pottery fragments, suggesting that the Hen Castell site was a major aristocratic stronghold which had been used by the local nobility for several centuries prior to the Norman invasion. Because of these finds it has been suggested that Hen Castell was a royal seat used by a more permanent `subregulus` based in the kingdom of Glywysing (which later became Morgannwg). 11 As noted elsewhere, this would have necessitated visits between several centres.

In later medieval times it became more closely associated with a local cantref or commote which was to be dominated by the Princes of Afan Wallia.

Collection of finds from the 1991 archaeological survey on the Hen Castell site.

Courtesy of Heneb

While the above finds appear to show a continuity of use at Hen Castell from the 4th to 12th centuries, its relevance to the Princes of Afan era relates to its use during the 12th century, described by archaeologists excavating the site in 1991 as being

`one of the relatively few early medieval sites in western Britan which became castles in the high medieval period`.

They list Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, of King Arthur renown, as another example, adding further:

`In the late 12th century it was the seat of a local ruler of a territory’

with confirmation from Gerald of Wales that this ruler was

`Morgan ap Caradog, Prince of those parts`.

Pen Castell

This is the third of the ‘castles’ mentioned by Anthony Thomas in Edward Lhuyd’s Parochialia, an Iron Age fortification, built by the Silures. 12 It was ideally placed to defend what would have been an important crossing on the River Afan, near the site of St. Michael`s church. In the middle part of the 12th century it was on the extreme eastern border between the Norman controlled lands in Tir Iarll and the Welsh controlled territory of Afan to the west and although it does not seem to have been further fortified by Caradog and his descendants, it is likely to have been the scene of hostilities between these two factions, who were fighting for control of the site. Even today an aerial view of the location shows concentric defensive ditches on top of the hill which could have been utilised by any military groups occupying the site. The 19th century poet and writer Madog Fychan gave the following description of Pen Castell in his book on place names in the Afan Valley, written in 1889.

‘At the top of the round hill there are traces remaining that suggest that some kind of fortification once stood there. It is a bare hill with a somewhat flattened top around which the tracks of a number of paths are plainly visible. Recently in ploughing the land, pieces of iron were turned up which appear to have been parts of some kind of weapon. Close to the farmhouse, there is an enormous stone just by the path that leads up to Penlan Walby and there is a tradition that many bodies are buried around it.’ 13

To add to this, I remember having a conversation with someone a few years back who described, when they were a young boy, finding an iron sword handle whilst playing on the top of Pen Castell in the 1970s; it was half-hidden under a rock. There is also a local legend linking Pen Castell to the daughter of a local Welsh prince, her name being Gwenllian. The story claims that the local lord, Rhys Fychan, lost a battle on the mountain close by [assumed to be Pen Castell], and that the Norman victor claimed Rhys`s daughter Gwenllian as his bride. But rather than marry her father`s enemy, she threw herself into a pool on the river Afan, where she drowned. The pool has, from that day on, been called Pwll Gwenllian, located near the old piggery site in Cwmafan. 14

It is said today that in times of flood Princess Gwenllian appears by night, dressed in flowing white robes, to warn of the danger. The ghost of her father is also said to guard the final resting place of his warriors, along with their buried treasure under a stone called Y Garreg Fawr.

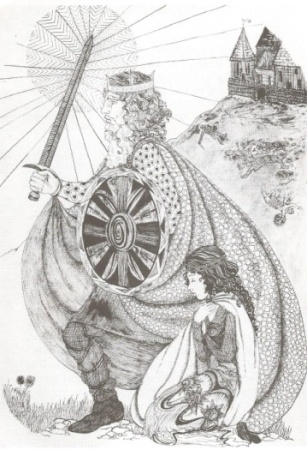

Gwenllian with her father. Drawing by Sandra Felstead from Elen and the Goblin and other Legends of Afan retold by Sally Roberts Jones 1977

Courtesy of Alun Books

Newcastle, Bridgend

Although only briefly occupied by the Princes of Afan, and some distance away from their ancestral homes at Aberafan and Plas Baglan, this castle should be included, firstly because of the way in which it seems to have come into the possession of that family, and secondly because it is the only castle still standing, at least in part, which is connected with them.

Newcastle was begun c.1106, but what now remains dates from almost a century later. This work may have begun just before the death of William of Gloucester, and been continued by Henry II; whether Morgan ap Caradog also contributed to the building is unknown, but it is possible that he did. As to how he came into possession of Newcastle, it seems to have been as an attempt at conciliation by King John. When William of Gloucester died in 1183, leaving three daughters as his heirs, Henry II, who was looking for a way to endow his youngest son, John `Lackland`, seized the opportunity and gave one of the daughters, Isabella, to John as his wife. It seems to have been a political marriage; the pair had no children and John divorced his wife in 1200, but it meant that he became Lord of Glamorgan, and in 1199 King of England in succession to his brother Richard I. His father had died in 1189, and in that year John gave the fee of Newcastle to Morgan ap Caradoc.

No doubt he already knew he could need allies, and who better than someone who commanded two vital river crossings on the way to Ireland.

The ornamented gateway of Newcastle in Bridgend. Photo: Tim Rees

For the moment this very necessary attempt at conciliation was successful. The death of Earl William in 1183 had led to a major offensive against the Norman settlements in Morgannwg; Henry II then warned the leaders – Rhys ap Gruffudd, the sons of Ifor Bach of Senghenydd and Morgan ap Caradog – against harassing the monks of Margam Abbey, though it was Cardiff, Newcastle, Neath and Kenfig which had suffered worst. (This was something of a family party since all those concerned – even William of Gloucester – were related; Gruffudd ap Ifor Bach was married to William`s sister, Mabilla).

Morgan ap Caradog was succeeded by his eldest son, Lleision, and in 1204 Lleision took 200 Welshmen to Normandy in the king`s service. But Lleision had died by 1217, when King John himself died. By then the Lordship of Glamorgan had reverted to Richard de Clare, who had married Isabella`s sister Amice, and then to their son Gilbert, who now took Newcastle from Lleision`s brother Morgan Gam and gave it to Gilbert de Turberville.15

Having to relinquish Newcastle seems to have caused great anguish to Morgan Gam, who appears to have been deeply affronted by its loss and harboured a strong desire to repossess it. Evidence of this is the numerous armed campaigns in the surrounding districts right up to his death in 1241. Ironically his military campaigns to try to reappropriate Newcastle were directed against his son-in-law Gilbert de Turberville, who had married his daughter Matilda.

Newcastle castle Bridgend, occupied by the Princes of Afan until c. 1217.

Photo: Tim Rees

REFERENCES

1. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales: Inventory of the Ancient Monuments of Glamorgan, 1991, Vol 3, (Part 1a), pp 154-6

2.O`BRIEN, James, Old Afan and Margam, The Author, 1926, p. 59

3. JONES, Thomas, ed, Brut y Twysogion or The Chronicles of the Princes, Peniarth MS 20 Version University of Wales Press, 1952, p. 58

O`BRIEN p.57

4. PHILLIPS, D. Rhys, The History of the Vale of Neath The Author, 1925, pp. 646-7

5.PHILLIPS, Martin. Folklore of the Afan District in Transactions of the Aberavon and Margam District Historical Society, 1932-3, pp. 102-3

6. RCAHMW, Inventory, 1991, Vol. 3, (Part 1a), p. 144

7. WILLIAMS, Rev J. (ab Ithel) ed. Annales Cambriae, Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts, 1860, p. 86

GILES, J. ed. Matthew Paris: Chronica Majora, pp. 406-9

Evans, A.L. Margam Abbey, The Author, 1958, pp. 72-3

8. WILKINSON, P.F., Excavations at Hen Castell, Briton Ferry, Glamorgan in Medieval Archaeology, Vol. 39, pp. 1-50

9. GERALD OF WALES, The Journey Through Wales, Penguin Books, 1978, pp. 130-131

10. RCAHMW. Vol. 3, (Part 1a), Pencastell

11. P. F. Wilkinson, E. Campbell, D. R. Evans, J. K. Knight, G. Lloyd-Morgan, M. Locock & M. Rednap (1995) Excavations at Hen Gastell, Briton Ferry, West Glamorgan, 1991–92, Medieval Archaeology, 39:1, 1-50, DOI: 10.1080/00766097.1995.11735573

12. ROWLANDS, Graham Place Names of the Afan Valley, Corlannau Press, NY, 2004, p. 48. (Edited translation of: Madog Fychan (David Evans), Hanes ac Enwau Lleoedd ac Amaethdau yn Nyffryn Afan, 1889, edited and translated by Graham Rowlands)

13. PHILLIPS, M. Transactions, 1932-3, p.85

14. EVANS, A.L. The Lords of Afan in Transactions of the Port Talbot Historical Society, Vol. 1, No. 3, 1974, pp. 25-27