Princes of Afan

- Princes of Afan

- Chapter 1: Villains or Heroes?

- Chapter 2: Seals of Office

- Chapter 3: The Aberafan Charter, c.1306

- Chapter 4: Where they lived

- Chapter 5: Where They Worshipped

- Chapter 6: Other Local Sites Associated with the Afan Dynasty

- Chapter 7: Ieuan Gethin and Other Poets at Plas Baglan

- Chapter 8: Time Line of Events Relating to the Princes of Afan

- Chapter 9: Princes of Afan in the Wider Context

- Chapter 10: The End of the Dynasty at Aberafan

Chapter 7: Ieuan Gethin and Other Poets at Plas Baglan

“A doughty fighter and a master of biting verse” 1

Ieuan Gethin was categorised as being part of a `talented literary minded class of gentry to whom the composition of poetry, notwithstanding their manifest expertise in the art, was essentially a pleasurable pastime and not an indispensable means of acquiring a living.` 2

It is generally acknowledged that Ieuan Gethin had access to some of the classic Welsh `prophesy poems` attributed to the likes of the 6th century bards Taliesin, Myrddin and others down the ages. His mother Elen was from Welsh nobility, based at the culturally renowned house of Aberpergwm in Glynneath, where a contemporary and relative of Ieuan Gethin, Rhys ap Siencyn, took a genuine interest in ancient bardic lore. It appears that he had access to manuscripts that contained compositions from Y Gogynfeirdd, a name synonymous with that of Beirdd y Tywysogion (Poets of the Princes), whose poems were created between the 12th and 14th centuries, celebrating the military feats of the Welsh princes. 3

Only ten of Ieuan Gethin`s poems have survived, but their subject matter varies greatly, being quite different from his professional contemporaries. There are several humorous narrative poems where he portrays himself as an old man to whom unforeseen events occur. These include a fox taking the goose which he had fattened for Christmas, where he humorously describes his friend Gwenllian, armed with a pitchfork, chasing the robber of the Christmas goose. Another poem describes a painful personal experience he had after catching a venereal disease following an encounter with a beautiful young woman. 4

Another poem which depicts the humorous side of Ieuan Gethin`s personality relates to the theft of wild bees` nests located in woodland surrounding his home at Plas Baglan.

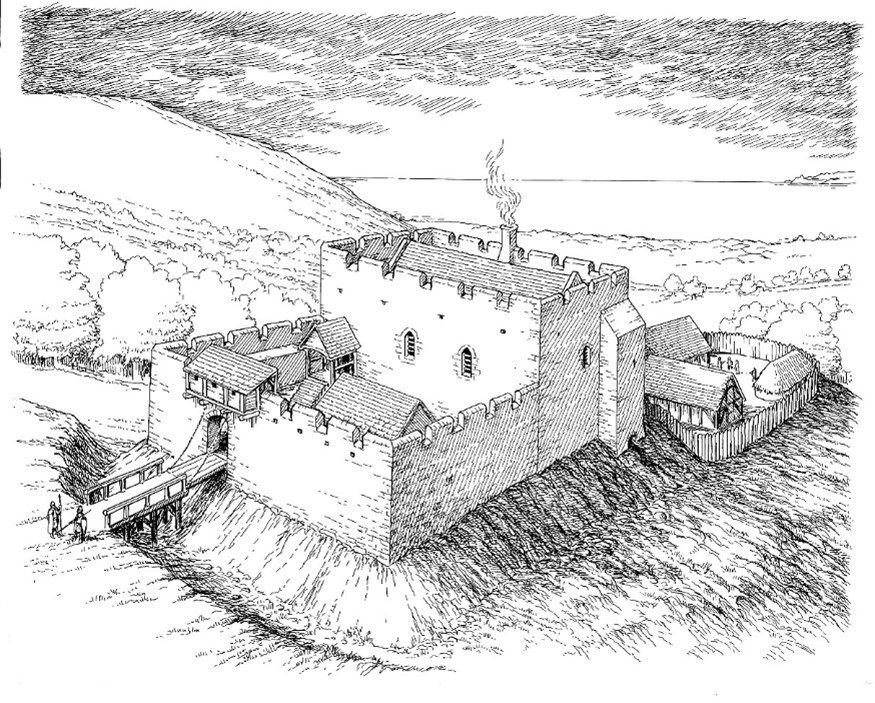

A suggested reconstruction of Plas Baglan seen from the north, by Paul R Davis

(from Towers of Defiance Y Lolfa 2021).

It is entitled ‘Kywyddyr Bydafe’, and in it the poet accuses individuals from the Vale of Neath of stealing bees’ nests from his trees. The poem is essentially full of Welsh bardic humour, describing the exploits of three individuals, Llywelyn, Gruffudd and Ieuan, who, it is suggested, have been sent by a young Lord Sion ap Rhys ap Shenkin of Aberpergwm in the neighbouring Vale of Neath to steal honey from trees belonging to Ieuan Gethin. Despite its humorous composition the words of the poem also have a stern warning for the honey thieves, described by Ieuan Gethin as `vermin and pests`, whom he threatens with legal action if they are caught in the act, describing how one of his men, whom he calls Dewi, will use his axe to cut off the offender`s foot or leg as he climbs the tree where the bees` nest is located.

Bees nest in a tree near Plas Baglan today

Photo by Paula Denby

A remarkable poem of relevance to national events relates to the imprisonment of Owain Tudor of Penmynydd, Anglesey, the grandfather of Henry VII, founder of the Tudor dynasty. This lament, c.1437, depicts the anger of the poet at Owain Tudor`s imprisonment; it starts with memories of his own sufferings in exile, in which he utters a prayer for this “flower” of a house that had befriended him. (The oldest surviving copy of this poem is kept at the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth.)

Two sad and poignant poems relate to the deaths of his own children who had died of the plague. The very personal response to his loss expressed in these poems makes it all the easier to empathise with his grief. The lament describes his children as his `Tegannau` – likening them to his jewels/playthings:

“Evan, Morfydd, Dafydd and Dyddgu, blighted by festering sores the size of shillings, boiling like hot coals, apples full of wrath, sad is this master of biting verse, his precious jewels lost forever.” 5

This sorrowful description of the children could only have been made by the hand of love, anxiety and grief.

Ieuan Gethin`s death prompted a great outpouring of grief amongst his fellow bards, one of whom, Iorwerth Fynglwyd, composed an elegy 6 which stands as a touchingly beautiful tribute to him. In translation:

“His death broke the bow of the muse:

The court of Llan Baglan was garbed in trappings of woe

And even the bards ceased their song,

Dark night having enveloped everything.

The mead brewed at Neath no longer had any attraction for the poet,

Laughter, song and gifts were wanting.

Every fair maid, and even the well-fed dogs and favourite steed mourned their master;

The Solomon of the poets and the prophet of Baglan was no more.

Ieuan Gethin was a saint, and with him the saints in heaven were singing.”

The Port Talbot historian Sally Roberts Jones comments in her thesis on the literary history of the Afan Nedd district:

“Ieuan Gethin was a poet himself, but as a descendant of the Lords of Afan, he was also a patron and welcomed other poets to his home at Plas Baglan. It is worth stressing that Ieuan Gethin was of princely ancestry.” 7

Picking up on the reference to Plas Baglan being a patron of other Welsh poets she reminds the reader of the assertion by Iolo Morganwg that one of the more controversial bardic scenes in Welsh medieval poetry was performed at Plas Baglan, involving the great medieval Welsh poet Dafydd ap Gwilym and a poet by the name of Rhys Meigen, who engaged in a form of poetry or `battle of wits` known as Cyff Cler. This was a tradition which involved a bard being the butt of ridicule and jest at the behest of his fellow poets.

Hence we have the tale of the poet Dafydd ap Gwilym arriving at Plas Baglan for an eisteddfod in the lifetime of Ieuan`s father, Lleision. Another bard, Rhys Meigen, was also present and ridiculed and insulted Dafydd, who duly replied at another eisteddfod in Emlyn the following year; the new poem was so biting in its satire that Rhys Meigen fell dead on the spot.

The following verse allegedly uttered by Meigen at Plas Baglan, which consequently led to his later sudden death, made veiled allusions to the circumstances of the great poet`s birth:

Mil, tri chant, meddant i mi – y ganwyd

Yn genaw dan lwyni

Gwr o`th han garw`th enwi

Mab Gwilym Gam gydgam, gi.

When Christ was thirteen hundred years old

Was born a base child, so I`m told;

And if the cub must bear a name

Swear it to Will, ycleft the Lame! 8

It should be acknowledged that the assertion maintaining these events unfolded at Plas Baglan is generally frowned upon by academics, with the general assumption being that Iolo Morganwg made the association after reading about a genuine poetical altercation between Ieuan Gethin and another man named Rhys, possibly the Rhys ap Siancyn of Aberpergwm referred to earlier.

As noted above, Ieuan Gethin, the descendant of princes and himself a member of the gentry, had no need to become a professional poet. An example of the latter group was Gruffudd ap Maredudd, better known as Casnodyn. 9 Born and raised in Cilfai (Kilvey), an area under the direct control of the Lords of Afan, he was noted for his skill in the traditional strict metres of Welsh verse. Whether he came often to Plas Baglan is not known, but such visits would have been part of his professional duties. He would have had a wide knowledge of Wales itself, of its historical lore, its place names and the genealogies of its ancient families, all of which contributed to the fabric of his learned poetry; the calls of patrons and prospects of employment would have required him as a young man to treat most of Wales as his own parish, embarking on what was known as a cylch Cymru, travelling around Wales, obtaining a sort of poetry apprenticeship through entertaining the uchelwyr or noblest families of the country. Casnodyn`s observance of the strict forms of Welsh verse has been recognised in the Oxford Companion to the Literature of Wales as follows:

‘This scholarly exponent of an ancient tradition frequently inveighed against the low standards of the poetasters, making it clear that he would not be counted among their number.’

Aberafan Beach and Cilfai Hill in the background, where Casnodyn was born; both areas were under the control of the Princes/Lords of Afan until the mid 14th century

There can be little doubt that in the first few decades of the 14th century the residents of Plas Baglan, ancestral home to the last Welsh princes of Morgannwg, would have been entertained by poets such as Casnodyn. By virtue of their training they were the custodians of the rich cultural traditions of the old kingdom of Morgannwg, their bardic knowledge devoutly passed on generation after generation, their rights and lore jealously guarded.

Saunders Lewis, one of the greatest Welsh literary figures of the 20th century, referred to the poetry composed by Ieuan Gethin and his fellows as displaying:

‘A majestic body of thought and meditation on the values of their society which has a lasting value, presenting a rich picture of a stable civilisation. Their function was to meditate continuously on this civilisation and to add quietly to it, transmitting their portrait of it from age to age.’ 10

Ieuan Gethin`s poems provide the literary historian with an interesting example of a cultured member of the aristocracy who had mastered the intricacies of the bardic craft.

IEUAN GETHIN`S CYWYDD TO OWAIN TUDOR, Circa 1437 11

Ieuan Gethin begins the poem with a reminiscence of his own sufferings in exile and utters a prayer for this `flower` of a house that had befriended him. If, as reported, Owain`s feet were held in irons, Ieuan Gethin with his teeth would unloose them in song. He further states:

‘The arrest is not for theft or treachery, not for horse stealing or debt, but for marrying the daughter of the King of the wine-land of France, from which union there has already issued valiant barons, grandsons of another monarch.’

He ends the cywydd by saying:

Y mab, mae gennym obaith,

A ddêl cynt o ddwylo caith.

Y dug hael glandeg o hyd

O lân Gaer Loyw a’n gweryd:

Cymrodedd Cymro ydiw

Â’i gariad gwych, garw du gwiw.

Rhoed Duw i’r gwalch balch bylchlyn

Fywyd hir i fyw at hyn.

Awch lid ei fwyall achlân

Enilled Owain allan

Yn rhwydd wrth yr arwyddion,

Yn rhydd i Benmynydd Mon!

“We have hope that the son of (Tydyr) will soon come out of their clutches. The keen anger of the handsome blackbird (Katherine, formerly Queen of England) should win Owain`s freedom; easily, too, by divinations; free for the sake of Penmynydd, Anglesey.”

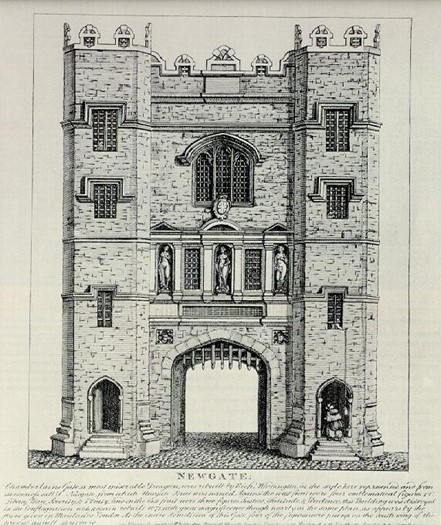

The old Newgate jail.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

REFERENCES

1. OWEN, Ann Parry, `An audacious man of beautiful words`: Ieuan Gethin (c. 1390- c.1470) in Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 2014, pp.1-39

2. LEWIS, C.W. The Literary Tradition of Morgannwg down to the Middle of the 16th century jn PUGH, T.B. ed Glamorgan County History, Vol. III, pp.497-499

PHILLIPS, D.R, The History of the Vale of Neath, The Author, 1926, pp.488-491

3. OWEN, Ann Parry, `An audacious man of beautiful words`: Ieuan Gethin (c. 1390- c.1470) in Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 2014, pp.1-39

4. OWEN, Ann Parry, Gwaith Ieuan Gethin. Aberystwth: Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies, 2013

PHILLIPS, D.R, pp. 471-479

5. JOHNSON, D. ed. Galar y Beirdd: Marwnadau`r Plant / Poets` Grief: Medieval Welsh Elegies For Children Tafol, 1993, pp. 72-5, 80-7

6. JONES, H. Ll and ROWLANDS, E. I. Gwaith Iorwerth Fynglwyd, University of Wales Press, 1975, poem 29

7. JONES, S,R. The Literary Tradition of the Neath and Afan Valleys, Maesteg and Porthcawl, M. Phil. Thesis, Swansea University, 2008, pp. 30-31

8. DAVIES, L. Outlines of the History of the Afan District, The Author, 1914, p. 64

9. STEPHENS, M. ed The New Companion to the Literature of Wales, University of Wales Press, 1998, p.93

10. STEPHENS, M. Wales in Quotations, University of Wales Press, 1999

11. OWEN, A.P. pp. 8-13, 23-26