Princes of Afan

- Princes of Afan

- Chapter 1: Villains or Heroes?

- Chapter 2: Seals of Office

- Chapter 3: The Aberafan Charter, c.1306

- Chapter 4: Where they lived

- Chapter 5: Where They Worshipped

- Chapter 6: Other Local Sites Associated with the Afan Dynasty

- Chapter 7: Ieuan Gethin and Other Poets at Plas Baglan

- Chapter 8: Time Line of Events Relating to the Princes of Afan

- Chapter 9: Princes of Afan in the Wider Context

- Chapter 10: The End of the Dynasty at Aberafan

Chapter 9: Princes of Afan in the Wider Context

Generally speaking, the Lords of Afan have been seen as something of a footnote to the medieval history of Wales. There has been one study of their history, by A. Leslie Evans, published in the Transactions of the Port Talbot Historical Society, and a more recent, so far unpublished, survey by Tim Rees. Both of these are particularly valuable in that their authors can draw on local knowledge, both geographical and historical, and are therefore uniquely qualified to show that the Lords – or, more appropriately, the Princes – of Afan were much more than defeated yes men. Indeed, at first sight it is remarkable how much they got away with, seemingly unpenalised, over the years. But as Princes, they were also players on the wider field of British history, and this too is part of their story. We start, therefore, by setting the scene against which Caradoc ap Iestyn and his family played out their parts.

The history of mediaeval Wales post 1066 tends to be seen in very black and white terms, with invading, victorious Normans and defeated, but heroic, Welsh princes. This is understandable. So little evidence, documentary or otherwise, has survived from the Welsh side that the historians` sources are almost entirely written from the English perspective. Even at the end of the period, in the 15th century, we have almost nothing from Owain Glyndwr and his government, so that as eminent a figure as R.R. Davies can speak of Glyndwr as `playing at prince in Harlech` or `sidling out of history`. Yet if we look at events in the wider context, a very different picture begins to emerge. This is particularly the case with the Lords of Afan, the princes who ruled in the west and north of what became the county of Glamorgan.

Perhaps one should begin by considering the early background of England and Wales. Though there had undoubtedly been conflict, archaeologists now suggest that the Anglo-Saxons came in as settlers rather than colonisers. Writers like Gildas and Bede speak of famine and plagues in the years following the recall of the Roman forces, and today we know only too well how much damage such afflictions can bring. There are still `lost villages`, where an entire community was wiped out in the Black Death of the fourteenth century. It is possible that the Saxon incomers were able to take advantage of a much-diminished population in their new home. However, though they interacted at times with the rulers of what was becoming Wales, they did not seriously attempt to add that territory to their own. Whether Offa`s Dyke was built for trade regulation or defence against the `wild Welsh`, it marks a border.

To begin with, `England` was made up of a number of kingdoms: Wessex, Mercia, Kent, Bernicia and Deira (later Northumbria) etc. These were independent, but at times acknowledged the pre-eminence of one particularly powerful ruler as an unofficial High King. Then, c. 800 AD, the Northmen, identified as Danes at that time, arrived. Alfred, King of Wessex, defeated them and under his immediate heirs, Edward and Athelstan, the kingdom of England slowly came into existence. But the Northmen were not done. In the 980s their attacks began again, and after the Battle of Maldon in 991 King Ethelred began to pay Danegeld, a form of blackmail to ensure peace. Then in 1013 Sweyn Forkbeard invaded, and Ethelred fled to Normandy (his second wife was Emma, sister of Richard II of Normandy). Sweyn died the following year, and Ethelred, and then Edmund Ironside, his son by his first, Saxon, wife, returned to England, but this was a brief respite. When Edmund died, Sweyn`s son Cnut became king. Edmund`s heir was a child and he and his brother were sent into exile, finally to Hungary, where he stayed until 1057. Meanwhile Emma had married Cnut and given him a son, Harthacnut. Cnut ruled Denmark, Norway and England, and when he died this legacy proved too much for Harthacnut, who removed to the Continent, leaving England to his half-brother Edward, known as `the Confessor`. He was Emma`s son by Ethelred and spent much of his early life in exile in Normandy, hence, when he became king, there was a strong degree of Norman influence at his court.

Edward died in January 1066, leaving no son to follow him. Edmund Ironside`s son had returned from Hungary in 1057, but died soon after, leaving a teenage son, Edgar the Atheling, and two daughters, Margaret and Christina. Edgar had grown up in exile, and though hs claim was considered, he made no attempt to take the throne. Instead the Witan, effectively the Parliament at that time, decided to give the crown to Harold Godwinsson, Edward`s brother-in-law, the most prominent of the Anglo-Saxon nobility. However the Northmen were still not finished. Harald Hardrada of Norway and William of Normandy both claimed the throne of England, though neither of them had a legal claim to the kingdom. Harald Hardrada based his claim on the fact that Harthacnut had made King Magnus, Harald`s father, his heir when he retired to the Continent, but since Canute, through whom this claim derived, had seized the throne, not inherited it, this was dubious at best. As for William, he had no claim by blood; Edward`s mother Emma was William`s great-aunt, but that was outside the Anglo-Saxon line of descent. William based his claim on the story, for which there was no other evidence than his word, that the Confessor had once promised him the throne. He also seems to have tricked Harold Godwinsson into swearing to uphold Wlliam`s claim when Harold was a hostage/guest at William`s court. Even if Edward had promised the crown to William, the Witan might well have disputed his right to do so.

Although the Northmen, or Vikings as they were also called, never set up a centralised empire on the Roman model, they were none the less, imperialists, with a vast trading network. They founded kingdoms in places as far apart as Sicily and Kiev in what is now Ukraine. Normandy was one of their colonies, founded by the Viking Rollo. His initial settlement gradually expanded into first a County and then a Dukedom, but placed as it was next to the long-established and much larger Kingdom of France, the opportunity for expansion was limited. William the Conqueror was Rollo`s great-great-great-grandson, and he saw that the situation in England, where its king had no heir, offered exactly the opportunity he craved.

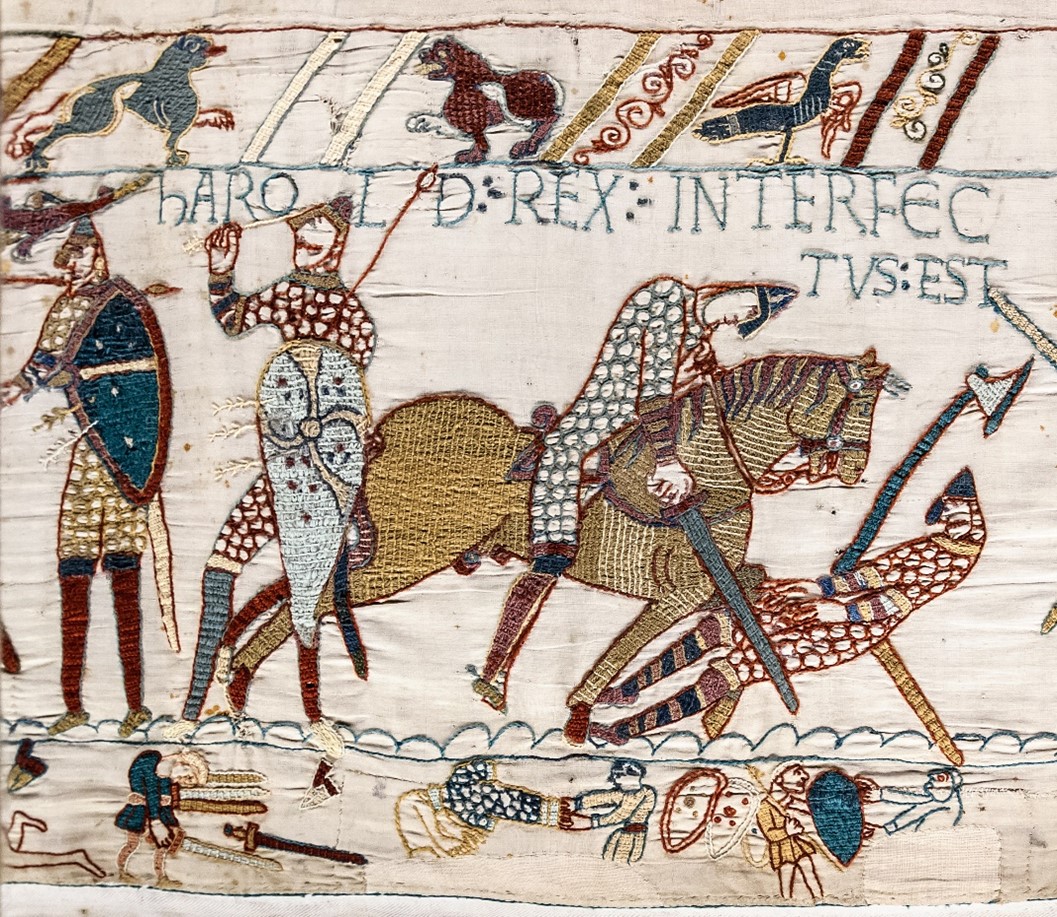

In the autumn of 1066 King Harold found himself facing invasions on two fronts. First Harald Hardrada attacked from the north, aided by Harold`s disaffected brother Tostig. Harold headed north and defeated Hardrada at Stamford Bridge, only to find that William of Normandy had taken advantage of a favourable wind and landed on the south coast. Harold marched to meet him, and though his army was not at its peak after the battle and the journey to Sussex, they gave a good account of themselves. But Norman tactics and the death of Harold during the battle, left William triumphant. There was no-one to take Harold`s place, and bearing in mind that few, if any, of the nobility of England trace their families back to Saxon origins, it would seem that most of his fellow nobles died with him.

Death of Harold, Battle of Hastings, Bayeux Tapestry

Myrabella, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

William wasted no time in confirming his victory and taking over his new colony – because that was what England now became. (We forget this now because Normandy itself was lost a century and a half later and the headquarters of the new empire were moved to London.) Whether William, unlike his Saxon predecessors, had plans to expand still further and absorb Wales too – or even Ireland – into his realm we do not know, though he made a pilgrimage to St. David`s which could have been a way of reconnoitring the possibilities. However William had no standing army and he had recruited various other lords and mercenaries for his campaign. These men had to be rewarded, which was easily done with the confiscated property of the defeated Saxons. This was enough for most of his followers, but there were some, the more powerful of those who had joined him, who might pose a problem. William was an adventurer, his claim to the throne was dubious, and might give ideas to men like the de Montgomeries.

William`s solution was to send them to the borders where they could act as a defence force; if they were able to expand their holdings into Wales, well and good – by feudal custom they held ultimately under the king. In Chester he placed Hugh d`Avranches (Hugh Lupus), who remained loyal. The Earldom of Hereford was given to William FitzOsbern, the king`s cousin and his one-time guardian; he was trusted, but he died in 1071, and his son, Roger de Breteuil, was part of the Revolt of the Earls in 1075. Roger was imprisoned and not released until after William`s death in 1087. However his father had already begun to move into Wales, building the first Chepstow Castle and then moving into Gwent before his own death. Chepstow Castle, unlike most other Norman fortresses, was built in stone from the beginning, which suggests that it was intended to be the headquarters of a major drive into Wales; but FitzOsbern`s death in battle in 1071 seems to have put an end to that for the moment. Chepstow came under royal control and William had more than enough to do in pacifying and organising his realm in England and defending Normandy from the King of France.

At that moment Wales was still split, as England had been, into a number of kingdoms. Although from time to time one ruler would gather a large part of the country into one unit, through inheritance, marriage or conquest, Welsh law did not include primogeniture and the unified kingdom would break apart again after his death, split between the king`s sons. (They might not all take part in the sharing out, but they all had a right to do so.) There were two main kingdoms: Gwynedd in the north, behind the bulwark of Eryri, and Deheubarth in the south west. Powys, on the eastern border, existed, but because of its long border with England, was less of a player nationally. In the south there were Gwent, which fell to the Normans under FitzOsbern by about 1070, Morgannwg, and a little further north Brycheiniog. Rhys ap Tewdwr was King of Deheubarth, Bleddyn ap Maenarch was King of Brycheiniog, and Iestyn ap Gwrgan King of Morgannwg.

Bernard de Neufmarche was probably too young to have taken part at Hastings in 1066 but he later, c.1087, gained lands in Herefordshire; he married the grand-daughter of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn and Edith of Mercia. In 1088, after the Conqueror`s death, he took part in a rebellion which aimed to put Robert, the Conqueror`s eldest son, on the throne instead of William Rufus. The rebellion was defeated, but those who took part seem to have suffered no penalty. Next Bernard turned his attention to Wales – perhaps this was why he escaped the king`s vengeance – and had reached Usk by 1091. He then moved on towards Brecon, and by 1093 he was confronting Bleddyn ap Maenarch, king of Brycheinog; Bleddyn appealed to Rhys ap Tewdwr, king of Deheubarth, for help, but in the battle that followed Rhys was killed and Bleddyn died soon afterwards. This left the way to Deheubarth open and Arnulph de Montgomerie, brother of Roger, Earl of Shrewsbury, struck down through mid-Wales to Pembroke, where in 1093 he began to build a castle. This rapid takeover of mid and south-west Wales, not the romance of the Twelve Knights, was the background to the story of the Princes of Afan.

It was apparently one of the Stradlings, in 1561, who created the story of the Twelve Knights of Glamorgan; his family did not arrive in the area until well after the original Norman incursion, but he wished to establish them as part of the original Conquest aristocracy. Whether there was any truth in his story is unknown, and it may have been further complicated later by Iolo Morganwg. Writers are like oysters growing pearls – they need a piece of fact to start the process going, but after that, who knows which of the facts was true? There is, however, just enough evidence left to show that the story of the Twelve Knights is simply that – a story. It is, however, worth recording here, as it introduces Iestyn ap Gwrgan, the ancestor of the princes of Afan.

According to the legend Iestyn, king of Morgannwg, was in conflict with Rhys ap Tewdwr. King of Deheubarth; Iestyn felt he needed a larger army, and so asked his relative, Einion ap Collwyn, who was at the time in England, to recruit more soldiers; in return Einion would be given Iestyn`s daughter as his wife. Einion duly recruited Robert Fitzhamon,and his twelve knights, a battle was fought at Penrhys in the Rhondda, and Rhys was killed. Iestyn then paid the Normans, but refused to hand over his daughter to Einion, who called back the departing Normans. They defeated Iestyn and took over Morgannwg, leaving Einion without either bride or financial reward.

Iestyn was a descendant of Rhodri Mawr, c.820-878, a slightly older contemporary of King Alfred, one of those rulers who had come near to creating a single kingdom in Wales, and who was the ancestor of most of the princely houses of the country (today even including the Windsors). Little is known about Iestyn himself who would seem to have been insignificant until he became king of Glamorgan in 1081, succeeding Caradog ap Gruffydd, and his reign was relatively short, ending c. 1091 when the Normans seized his kingdom. His headquarters may have been originally at Cardiff, and there are suggestions that he may have built the first Kenfig Castle. He is said to have been married at least twice, firstly to Denis, by whom he had several children, and then to Angharad – sometimes called Constance – the daughter (or grand-daughter) of Elystan Glodrydd, by whom he also had children. Some sources also add a third wife, Dyddgu, by whom he had no children. This is further complicated by the fact that there were apparently as many as three Iestyn ap Gwrgans at about the same time. Curiously, Caradoc, who was his main heir, is noted as the son of the second marriage, to Angharad – though Denis is an odd name for a Welsh woman at that period, and it has even been suggested that it is a misunderstanding of the name Dinas, as in Dinas Powys, where he may have had a court, so that there was only one marriage. This would be of no particular relevance except that Sir Richard de Granville, the founder of Neath Abbey, lieutenant and possibly brother of Robert Fitzhamon, whom we shall encounter shortly, had a Welsh wife called Constance, possibly the wife or sister of Iestyn ap Gwrgan.. Iestyn himself drops out of sight c. 1091-1093, perhap as a result of the Norman incursion, though his disappearance probably had no immediate connection with Rhys ap Tewdwr`s defeat at Brecon, He is said to have retired to `Censam`, a religious foundation – it has usually been transcribed as `Keynsham`, though that abbey was not founded until 1169; other destinations suggested include Llangernyw in North Wales, Llangennydd in Gower, and Llangenys, in Monmouthshire, where he was supposedly buried.

William I chose to leave his kingdom to his two eldest sons, Normandy to Robert and England to William Rufus; though Henry, the youngest son, was not landless, he did not inherit a kingdom of his own. William`s visit to St. David`s in 1081 may have been intended to let him reconnoitre the situation there and assess the possibilities of adding this area to his kingdom – or even of going further and invading Ireland. He did come to an agreement with Rhys ap Tewdwr, who swore fealty to him and later paid him £40 a year. From Rhys`s point of view, this gave him a useful ally against local rivals, and for William it helped to secure his borders. However, William`s barons were ambitious men – especially the Montgomerie/de Belleme alliance, and when William died in 1087, they rebelled in an attempt to put Robert on the throne of England instead of William Rufus. The rebellion was crushed, but in 1088 William Rufus gave the Gloucester lands, forfeited by Roger de Breteuil in an earlier rising, to Robert Fitzhamon, a cousin and supporter of the Conqueror. Fitzhamon duly moved steadily into Gwent and then the Vale of Glamorgan until he came to Kenfig. He had left the hill country, the blaenau, to the Welsh, which was wise; guerilla warfare rather than pitched battles was a speciality of Welsh armies, as Julius Caesar hd once discovered. For whatever reason, Fitzhamon seems to have faced little resistance in his advance until he reached the Afon Cynffig and this is where the history of the Princes of Afan begins.

Generally speaking, historians do not seem to have noted the considerable strategic importance of the Afan lordship. In fairness it was of less importance in a purely Welsh context, but as far as William and his successors were concerned, it was vital, controlling as it did, the main route to West Wales and beyond. At this point the mountains come down almost to the sea, and there were two river crossings, of the Afan and the Neath, plus a harbour at the old Bar of Afan. Both crossings, as we know from Gerald of Wales a few years later, could be a problem, even without the risk of attack by hostile forces from the hills, while the harbour meant that one could be supplied or reinforced from the sea, a very important factor at that time and place. One could, of course, cut down across mid-Wales, as Arnulf de Montgomerie and Bernard de Neufmarche did, but that had its own problems. And the road to the west had to be kept open so that the king of England could ensure that rebellious and ambitious barons did not take over Wales as a rival kingdom of their own, or, alternatively, that no rival power could use the route via Ireland and Wales to invade England. (The Romans had ignored that possibility because they already owned every likely rival, but the idea that it could be used as a launch platform for invaders has been the curse of Ireland ever since.)

We have no documentary evidence as to what happened when Fitzhamon reached the Kenfig area, but there is also no evidence of major conflict. In 1081 William I had negotiated with Rhys ap Tewdwr and in all probability Fitzhamon now negotiated with Caradoc ap Iestyn and his kin. From Caradoc`s point of view it avoided what would have been a bloody conflict and possible – probable? – defeat, and left him with a considerable degree of autonomy; he might now be holding under the king, but the king was far away, where men like the de Montgomeries were much closer to hand. For Fitzhamon too it avoided conflict and provided a useful ally. The Lordship of Afan was not the kingdom of Morgannwg, but it was substantial, consisting of the land between the rivers Afan and Nedd, and reaching far back into the blaenau. As for Fitzhamon and his successors, an agreement helped to avoid a messy guerrilla conflict and ensured that this strategic point remained within royal control.

We tend to think of the Normans as a solid block and perhaps that was mainly true under William I, but after that one can see the slow development of two groups: on the one side the king and his loyal supporters and on the other the barons, eager for more power and riches. This was not a hard and fast grouping, but it was something to be reckoned with, and for the Welsh, at least in this earlier period, the king offered the better option. He could be negotiated with, where the barons generally could not. It was Bernard de Neufmarche who was responsible for the death of Rhys ap Tewdwr, the de Braoses organised the massacre of Welsh lords at Abergavenny, and de Londres at Kidwelly ordered the execution of Princess Gwenllian and her son. The Afan princes were never tame Welshmen, but as the king`s subjects, they were treated with a degree of respect, people to be negotiated with, not simply ordered about like menial servants.

Through most of history, at least for the upper classes, marriage has been a matter of politics, not romance, hence the large number of royal bastards. However Wales had an advantage here, since illegitimacy was not a barrier in the way that it was in England; in Wales as long as the father acknowledged the child, it had the same rights as a child born in wedlock. This was something that was made use of by both sides. Since Wales was not a united kingdom in the way that Scotland had come to be, a marriage between a legitimate royal son and the daughter of a Welsh prince (or vice versa) would have been seen as a `disparagement` on the side of the royal partner. (Almost three hundred years later the chronicler Thomas of Walsingham felt that the marriage of Edmund Mortimer to Owain Glyndwr`s daughter Catrin was just such a disparagement.) But an illegitimate but recognised royal daughter was another matter, a useful diplomatic asset. The best-known example is the marriage of King John`s daughter Joan to Llywelyn ap Iorwerth – Llywelyn Fawr – but there is an equally useful example in the history of twelfth century Glamorgan.

Robert Fitzhamon campaigned in France as well as Wales, and in 1105 he was badly wounded; he survived for two more years, but he did not fully recover from his wounds, which may be why there appears to have been a lull in the move into western Morgannwg. Fitzhamon died in 1107, leaving a daughter, Mabilla, as his sole heir; she was still a child and the king`s ward, and King Henry decided to marry her to his eldest son, Robert. Robert himself was illegitimate, but acknowledged, and he was given the Gloucester lands that his father-in-law had held, becoming Earl of Gloucester in 1122. In the meantime Sir Richard de Granville acted as guardian of the Fitzhamon estates. There is no evidence of how he dealt with with Iestyn`s heirs, but his wife Constance, who was associated with him in the founding of Neath Abbey was apparently Welsh, and it has been suggested that she was either Iestyn`s widow or sister. If so, it suggests in turn that a policy of making alliances may have succeeded the use of naked force. Whether Robert of Gloucester`s still unknown mother had any link with Wales is not known (though she was certainly not Nest, Rhys ap Tewdwr`s daughter, as once suggested), but Robert took an interest in his Welsh lands, rebuilding Cardiff Castle in stone and founding Margam Abbey. Much of his time was spent elsewhere, defending his father`s French lands or, later, supporting his half-sister Maud in her fight for the English Crown, and it was his lieutenant, Sir Richard de Granville, who looked after the Welsh lands. (We tend to forget that in these early years the Normans were fighting on two sides, defending their lands in France and establishing themselves in Britain.)

Following the death of Rhys ap Tewdwr, his son Gruffydd, still a child, was spirited away to safety in Ireland, but Gruffydd`s sister Nest was taken hostage. She too was young, but in 1102 she bore a son to Henry, now King of England after the death of William Rufus. By then Henry was married, a marriage which not only linked him with Scotland, but also with the earlier Anglo-Saxon dynasty, since his wife, Matilda, was the daughter of Malcolm of Scotland and Margaret, the grand-daughter of Edmund Ironside. Possibly Matilda was less happy with Princess Nest at court than she seems to have been with Henry`s numerous other mistresses, but in any case, Nest was soon married off to Gerald of Windsor, who was the castellan of Pembroke Castle. Here too Henry was making a connection with the earlier rulers, and when Nest`s brother came back from Ireland and began to try to regain at least part of his father`s kingdom, he was apparently able to take shelter from time to time with his sister and her husband. Henry Fitzroy, Nest`s son by Henry I also strengthened the Welsh connection, becoming Lord of Narberth and Pebidiog in West Wales; his son Meilyr was part of Strongbow`s invasion of Ireland, and became Chief Justice of Ireland.

As it happens, Nest has been somewhat unfairly pictured as a lady of doubtful virtue. In practise it is likely that she had little choice when Henry I turned his attention to her, or when Owain ap Cadwgan carried her off from Cenarth Bychan Castle – on which occasion she helped her husband escape the intruders, and later returned to him. After Gerald`s death she married again. But `the Helen of Wales` makes a much better story than that of the faithful wife and whatever the truth of Nest`s life story, her marriage to Gerald was at the beginning of a network of alliances that was to play an interesting part in the early history of Norman South Wales. She was, to start with, the grandmother of Gerald of Wales, who gives us the fullest picture of twelfth century Wales that we have. He was, by birth and career, part of the Anglo-Norman establishment, but he was also fully aware of his Welsh heritage. Although Gerald does not say so, Morgan ap Caradoc, who escorted the Archbishop of Canterbury`s party through Afan, was Gerald`s cousin, and it is likely that his very full account of happenings in the area came not just from an evening spent as a guest at Margam Abbey, but also from family knowledge.

Princess Nest ferch Rhys in bed with Henry 1 of England

Illuminated Manuscript by Matthew Paris

Courtesy of The British Library

The marriage of Nest and Gerald of Windsor was the first of a network of alliances binding the princes of South Wales and the family of Henry I. As mentioned above, Nest`s brother Gruffydd ap Rhys returned from Ireland and began to try to regain the family kingdom. He had a somewhat chequered career as far as this was concerned, but eventually he did succeed in regaining the Cantref Mawr, effectively the Tywi Valley, and his heirs were able to build on this. He married twice, and among the children of his second marriage, to Gwenllian, sister of Owain Gwynedd, were two daughters, Gwladys and Nest. Gwladys became the wife of Caradoc ap Iestyn of Afan, and, Nest became the wife of the other major Welsh lord in Morgannwg, Ifor Bach of Senghenydd.

Meanwhile Robert of Gloucester had married Mabilla and assumed the lordship of Fitzhamon`s Welsh holdings; he and Mabilla had several children, including their heir, William, but Robert also had four illegitimate children, who were clearly accepted as part of the family – one became a bishop, one Castellan of Gloucester, and the daughter was even named Mabilla, which suggests a high degree of generosity on the part of Robert`s wife. She married Gruffydd, son of Ifor Bach of Senghenydd, who thus became the brother-in-law of William, second Earl of Gloucester. Gruffydd`s sister, Gwenllian, married Morgan ap Caradoc of Afan. At this early point such Norman-Welsh unions were not usual, and it suggests a willingness to negotiate. If Sir Richard de Granville`s wife Constance was indeed part of the family of Iestyn ap Gwrgan, then perhaps that marriage had opened up possibilities.

Pembroke Castle’s outer ward seen from the south

Mario Sánchez Prada from Staines, United Kingdom, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Circa 1158 Ifor Bach, angered by William of Gloucester infringing on Ifor`s lands, climbed into Cardiff Castle, seized William, his wife and his heir and carried them off into the hills until William made restitution. William was not noted for generosity as the sad story of Canaythan the hostage whom he had blinded when Morgan ap Caradoc displeased him, tells us. Yet Ifor Bach appears to have suffered no punishment for his action. Perhaps the family link did count for something. If so, then perhaps Neath (founded 1129) and Margam (1147) Abbeys were not, as accounts have recently proposed, built to contain the Lords of Afan, but to reinforce their command of the strategic Afan and Neath river crossings. Mabilla, granddaughter of Henry I, and her husband, Gruffydd of Senghenydd, chose to be buried at Margam Abbey.

We have almost no information about Caradoc ap Iestyn apart from a reference in Brut y Tywysogion for 1127 to Caradoc and two of his brothers committing an unspecified `deed of violence`. However there is one other reference, from 1153, to Aberafan Castle being attacked and burnt down by Rhys and Maredudd of Deheubarth, Morgan ap Caradoc`s brothers-in-law. This is puzzling, and has led to suggestions, particularly in recent years, that the castle was originally a Norman foundation, possibly actually built by Caradoc under the orders of Fitzhamon or his successors, and that the princes of Afan only became resident there in 1304 when Leisan de Avene issued a charter for the borough. However no Norman knight has ever been associated with Aberafan in the way that, for example, the Turbervilles were associated with Coity, and local tradition agrees that this was the castle of the Lords of Afan. Also, the attackers were said to have taken away vast quantities of plunder, which sounds unlikely for what would then have been a Norman garrison rather than a residence. Possibly the reference was an error, meant for another castle elsewhere. However there is another possibility. William of Gloucester, succeeding his father, seems to have wanted to assert his authority, as we see from the story of Ifor Bach of Senghenydd; was this a slightly earlier attempt to do this on William`s part, leading Morgan ap Caradoc`s brothers-in-law to come to his rescue?

FURTHER READING

• DAVIES, John, A History of Wales, Allen Lane. The Penguin Press, 1993

• DAVIES, R.R,, Conquest, co-existence and change 1063-1415, University of Wales Press,

• 1987

• DAVIS, Paul R. Towers of Defiance: the castles and fortifications of the Princes of Wales,

• Y Lolfa, 2021

• DAVIS, Paul R. Forgotten Castles of Wales and the Marches, Longaston Press, 2021

• EVANS, Gwynfor, Land of My Fathers, Y Lolfa, 1992

• GERALD OF WALES, The Itinerary Through Wales and the Description of Wales, Penguin Books, 2004

• MAUND, Kari, The Welsh Kings: Warriors. War Lords and Princes, The History Press, 2006

• MOORE, Donald., The Welsh Wars of Independence, Tempus, 2005

• Pugh T.B. ed. Glamorgan County History: Vol.III, The Middle Ages. Glamorgan County History Committee/University of Wales Press, 1971

• TURVEY, Roger, The Welsh Princes 1063-1283, Longman, 2002

• WILLIAMS, Gwyn, The Land Remembers, Faber & Faber, 1977

• WILLIAMS, Gwyn A. When was Wales? Black Raven Press, 1985